When suicidal urges surface, they can feel overwhelming and all-consuming. Thoughts arrive suddenly and with great intensity, leaving little space between the impulse and the despair that fuels it. In these moments, the ability to pause can make a profound difference. While professional support is essential, mindfulness practices can offer simple, grounding tools that help create that pause, anchor you in the present, and soften the grip of suicidal thinking.

Mindfulness will not erase pain, and it is not meant to replace therapy, medication, or crisis care. What it can do is help you notice your thoughts without immediately acting on them, reconnect with your body, and reclaim even a small sense of control when everything feels unbearable. Below are twelve practices, each explained in depth, with guidance about when they may help most and when they might not be the right fit.

Important, read that again: mindfulness is not going to replace crisis intervention. If you are in crisis and feeling suicidal, call 988 or reach out to someone you trust for help.

Find a Therapist

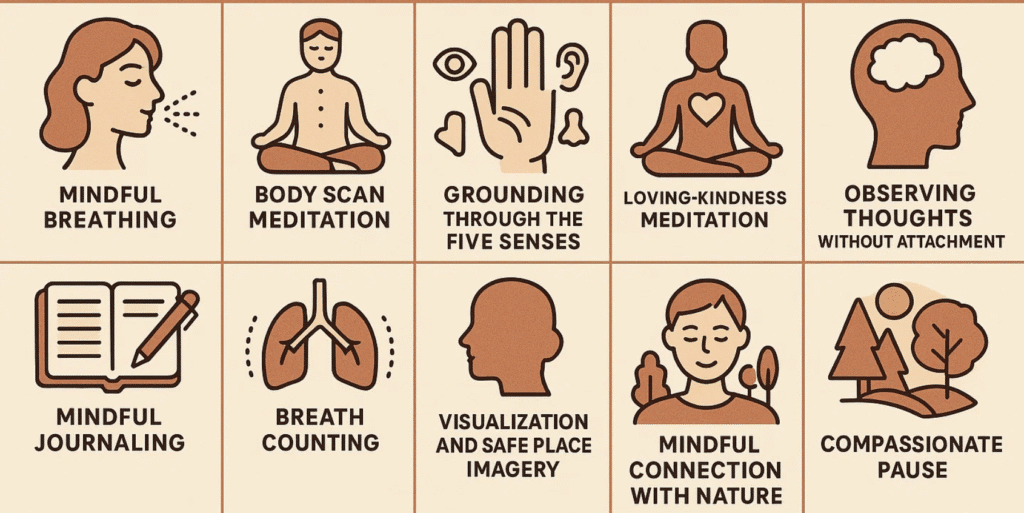

1. Mindful Breathing

Breath awareness is one of the oldest and most widely practiced forms of mindfulness, rooted in Buddhist meditation and supported by modern research. It works because the breath is always available, steady, and life-sustaining.

How to practice

Sit or lie down somewhere you feel reasonably safe. Bring your attention to your breathing. Notice the inhale, notice the exhale, and let the breath come and go at its own pace. If your mind wanders, gently return to the sensation of breathing. Even three to five breaths can be enough.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Suicidal thoughts often spiral quickly, creating a sense of urgency. The breath provides an anchor in the middle of that storm. Each inhale and exhale is proof that life is continuing in this moment, buying time between impulse and action.

Who/when it may help most

If your mind races and you feel flooded with thoughts, this practice can help create space and slow things down.

It might not be for you if

Focusing on your breath feels suffocating, panicky, or triggering. In that case, try grounding with your senses instead.

2. Body Scan Meditation

The body scan, popularized by Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), teaches awareness of physical sensations as a way of reinhabiting the body.

How to practice

Close your eyes if it feels safe. Slowly move your awareness from the top of your head down to your toes. Notice sensations—tension, numbness, tingling, heaviness—without trying to change them. Take your time, breathing gently as you go.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Suicidal urges often bring disconnection from the body, as if you are floating away or cut off. The body scan gently brings you back, reminding you that you exist here, now, in a living body.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel disconnected, dissociated, or like you are “not in your body,” this practice can restore grounding.

It might not be for you if

Certain body areas hold painful or traumatic memories. You can skip those places or choose another practice.

3. Grounding Through the Five Senses

This grounding practice is widely used in trauma therapy because it engages the senses to anchor awareness in the here and now.

How to practice

Look around and name five things you can see, four things you can feel, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. Go slowly and really notice each sensation.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

When suicidal thoughts pull you into past regrets or fears about the future, this practice snaps your attention back to the immediate present, which is often safer than the places your mind is trying to take you.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel overwhelmed, panicked, or trapped in racing thoughts, grounding through the senses can pull you back into your surroundings.

It might not be for you if

Your current environment feels unsafe or overstimulating. In that case, close your eyes and focus only on touch or sound.

4. Loving-Kindness Meditation

Loving-kindness (metta) meditation comes from Buddhist traditions and has been shown to increase compassion and reduce self-criticism.

How to practice

Sit comfortably and silently repeat phrases such as: “May I be safe. May I be at peace. May I live with ease.” If starting with yourself feels too hard, imagine a friend, loved one, or even a pet, and direct the phrases toward them first before including yourself.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Suicidal thoughts often come with deep self-criticism or shame. Loving-kindness gently replaces harsh inner voices with compassion, making it harder for suicidal thoughts to dominate.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel consumed by self-hatred or unworthiness, this practice can help soften your inner dialogue.

It might not be for you if

Hearing positive phrases directed at yourself feels unbearable or fake right now. Start with neutral figures or skip this practice for the moment.

5. Observing Thoughts Without Attachment

This practice is rooted in mindfulness and acceptance-based therapies, where the goal is to see thoughts as mental events rather than truths.

How to practice

When a thought arises, label it simply: “That’s a thought.” For example, when you think, “I want to die,” you can say to yourself, “This is a suicidal thought.” Imagine the thought floating by like a leaf on water.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Suicidal urges feel urgent because thoughts can seem like commands. This practice reminds you that thoughts are events in the mind, not orders you must obey.

Who/when it may help most

If suicidal thoughts feel constant and controlling, observing them in this way can weaken their power.

It might not be for you if

Labeling thoughts feels dismissive or makes you feel more disconnected. In that case, journaling may feel more validating.

6. Walking Meditation

Walking meditation, common in Zen and Theravāda traditions, combines mindfulness with gentle movement.

How to practice

Walk slowly and deliberately, paying attention to each step. Feel your foot touch the ground, lift, and step again. If your mind drifts, return to the rhythm of your steps.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Moving your body while focusing on each step channels restlessness or agitation into a safe, grounding rhythm. It also demonstrates physically that forward motion is possible, step by step.

Who/when it may help most

If sitting still makes you feel trapped or restless, this moving meditation can help you calm without having to be still.

It might not be for you if

Being outside alone feels unsafe. Try pacing mindfully indoors instead.

7. Mindful Journaling

Mindful journaling is a modern practice that blends mindfulness with expressive writing, offering a structured outlet for difficult thoughts.

How to practice

Take a notebook and write freely for five to ten minutes. Notice your thoughts and feelings without censoring them. Let the words flow, even if they seem messy. You can also use prompts like “Right now I feel…” or “One small thing keeping me here is…”

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Writing slows down racing thoughts and makes inner chaos visible on the page. Once written, urges can be observed rather than acted on. Journaling can also highlight patterns and moments of resilience you might not otherwise notice.

Who/when it may help most

If your head feels crowded and you need an outlet, journaling can help you release and organize what feels overwhelming.

It might not be for you if

Writing pulls you deeper into rumination. In that case, stick to shorter prompts or use a grounding exercise instead.

8. Breath Counting

Breath counting is often used in Zen meditation to build concentration and steady attention.

How to practice

Count each inhale and exhale up to ten, then start again. For example: inhale-one, exhale-two, inhale-three. If your mind wanders, gently begin again at one.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

The structure of counting occupies the mind enough to interrupt spirals. The rhythm of counting reinforces that you can survive one breath at a time.

Who/when it may help most

If you need something simple, repetitive, and structured to steady your mind in a crisis, this practice can be grounding.

It might not be for you if

Breath focus feels triggering or overwhelming. Try counting steps, sounds, or objects instead.

9. Visualization and Safe Place Imagery

This practice draws from guided imagery techniques in psychology, often used for trauma recovery and stress reduction.

How to practice

Close your eyes and imagine a place where you feel completely safe and calm. It could be real or imagined. Engage all five senses—see the colors, hear the sounds, feel the textures, notice the smells.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

When your current environment feels unbearable, a safe place in your mind can offer refuge and stability. Even a few minutes of visualization can shift your nervous system into calm.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel cornered by despair and need an immediate escape, this practice provides a mental refuge.

It might not be for you if

Imagination feels unsafe or brings up traumatic memories. In that case, focus on grounding with real sensory details around you.

10. Noting and Labeling

This technique comes from insight meditation (vipassanā), where thoughts and feelings are noted with gentle awareness.

How to practice

As experiences arise, mentally note them: “thinking,” “worrying,” “planning,” “remembering.” Keep the tone gentle and neutral. Then return to the present moment.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Labeling creates just enough distance between you and suicidal thoughts so they feel less consuming. It reminds you that you are more than your thoughts.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel swallowed up by mental chatter, this practice can give you perspective.

It might not be for you if

Labeling feels mechanical or cold. If that happens, try journaling or the compassionate pause instead.

11. Mindful Connection With Nature

Many mindfulness traditions emphasize the healing power of nature, and research confirms its impact on mood and resilience.

How to practice

Step outside or look through a window. Pay close attention to natural details—birds, trees, clouds, plants. Notice light, colors, sounds, and sensations of air on your skin.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Nature gently reminds you of cycles of change and renewal. Feeling connected to something larger than yourself can soften the isolation that fuels suicidal thinking.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel cut off, hopeless, or isolated, reconnecting with nature can bring perspective and grounding.

It might not be for you if

Being outside feels unsafe. A houseplant, a seashell, or even a photo of a favorite place can be used instead.

12. Compassionate Pause

The compassionate pause is a simple, modern practice used in self-compassion training to interrupt harsh self-criticism.

How to practice

Place a hand on your heart (or another comfortable spot), take a slow breath, and say to yourself, “This is hard. I am hurting. May I find peace.” Repeat gently until you feel even a slight softening.

How it helps in suicidal crisis

Suicidal urges are often driven by harsh self-judgment. The compassionate pause interrupts that cycle and replaces judgment with care. It reminds you that suffering deserves tenderness, not punishment.

Who/when it may help most

If you feel like you are attacking yourself internally, this practice can introduce compassion into that moment.

It might not be for you if

Self-touch feels uncomfortable. You can visualize warmth directed toward yourself, hug a pillow, or place your hands on a table instead.

Integrating Mindfulness Into Daily Life

These practices are most effective when practiced regularly, not only during emergencies. With time, they build muscle memory so that when suicidal urges arise, you already have familiar tools to draw on. Think of them as part of a wider safety net—alongside therapy, support systems, and medical care.

Why Mindfulness Matters for Suicide Prevention

Mindfulness restores agency. It creates a gap between thought and action—a gap where choice lives. That gap may be enough to reach out for help, recall a value, or simply survive another hour.

Mindfulness does not replace therapy, medication, social support, or crisis care. Instead, it complements these, providing accessible skills that reinforce resilience and presence.

Moving Forward

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, immediate help is available through the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. For ongoing care, therapy provides a safe space to explore mindfulness alongside deeper healing work.

At our practice, several associate therapists integrate mindfulness into treatment as one element of a broader, compassionate approach to suicidality. We invite you to explore our therapist directory to find support tailored to your needs.

FAQ: Mindfulness for Suicidal Crisis

Is mindfulness safe to use during an acute suicidal crisis?

Mindfulness can help create a brief pause, but it should not replace crisis care. If you feel at immediate risk, contact emergency services or the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline first, then use very short grounding practices while you wait or while you connect with support. Think in thirty- to sixty-second doses: feel your feet on the floor, name three sounds, take three slow breaths with longer exhales. Treat mindfulness as a seatbelt, not the entire vehicle.

How do I choose which practice to use in the moment?

Use a simple decision rule. If your mind is racing, choose a focus practice such as breath counting or noting. If you feel numb or far away, choose a sensory or movement practice such as five-senses grounding or slow walking. If shame is loud, choose a compassion practice such as the compassionate pause or a short loving-kindness phrase. If an environment is unsafe or overstimulating, use internal anchors like feeling your hands together or silently labeling “safe now, safe enough.”

What if mindfulness makes me feel worse or more aware of pain?

Switch from inward-focused attention to outward-focused grounding. Look around the room and name colors, textures, or shapes. Add gentle movement, such as standing, stretching, or walking. If attention to breath intensifies panic, shift to counting objects, tapping fingers, or placing a cool cloth on your face. Your goal is not perfect calm; it is enough steadiness to choose the next safe step, such as texting a support person or following your safety plan.

Can mindfulness help with dissociation or numbness?

Yes, but choose practices that re-engage the senses and muscles. Press your feet into the floor, hold a warm mug, run cool water over your hands, or push palms against a wall and notice muscle activation. Call out loud what you see to re-orient yourself, for example “door, window, lamp.” Keep your eyes open and lights on. Avoid long, eyes-closed meditations until you feel back in your body.

What can I do when intrusive images or “command” thoughts show up?

Use quick cognitive defusion. Silently say “I am noticing the thought that…” and then repeat the intrusive line verbatim. This puts a little space between you and the thought. Pair it with a physical anchor such as holding a cold object or stomping your feet. If images are vivid, try brief rescripting: picture a stop sign, change the scene’s colors to grayscale, or imagine a trusted person entering the image and ushering you out. Then take one supportive action from your plan, such as sending a check-in message.

How do I downshift panic-level arousal fast enough to prevent acting on an urge?

Lengthen your exhale, for example inhale to a count of four, exhale to a count of six or seven. Splash cold water on your face or hold a cold pack against your cheeks for thirty seconds to trigger a calming reflex. Do brief isometric holds such as a steady wall push for ten to twenty seconds, then release and notice the after-calm. Follow with a grounding statement like “I can ride this wave; it will crest and fall.”

Can mindfulness help at night when urges spike and I cannot sleep?

Create a bedside sequence you can do in the dark. Place both feet on the floor, name five things you can feel, take three slow breaths with longer exhales, then do a two-minute body scan from toes to scalp. Keep a small notebook to offload looping thoughts with one-line entries such as “At 2:10 am I feel X. Next tiny step: text my therapist at 8 am.” Have your safety plan and numbers within reach so you do not have to search while distressed.

How does mindfulness fit with medication or other treatments?

Mindfulness can increase your ability to notice what helps and when. Track how practices feel at different times relative to medication, for example thirty minutes after a dose you might find breath counting easier. If a medication causes restlessness or drowsiness, choose matching practices such as walking meditation for restlessness or five-senses grounding for grogginess. Share observations with your prescriber so your plan can be tuned to your lived experience.

I have ADHD or I am autistic. How can I adapt mindfulness?

Shorten practice windows to thirty to ninety seconds and repeat them often. Replace stillness with structured movement such as step-counting, fidgeting intentionally, or gentle rocking while you name sensations. Use clear, concrete prompts rather than abstract ones, for example “notice three blue things” instead of “observe without judgment.” If certain sensations are aversive, build a personalized sensory kit with preferred textures, temperatures, and sounds.

I come from a spiritual or cultural tradition that does not use the word “mindfulness.” Can I still benefit?

Absolutely. Use the words and practices that fit your world. Prayer, recitation, brief ritual, and nature-based attention are parallel forms of mindful presence. If a phrase like “May I be safe” does not resonate, borrow language from your tradition or values, for example “Steady my heart,” “I am held by my people,” or “I walk with dignity.”

Are apps or recordings useful during crisis, or can they be overwhelming?

They can help if you prepare ahead. Download two or three short, offline guides so you are not hunting during distress. Set up a favorites folder with ten-minute or shorter audios and label them by purpose such as sleep, panic, compassion. Turn off autoplay and comments to avoid overstimulation. If voices feel intrusive in crisis, use silent timers and written prompts instead.

How do I know if these practices are helping?

Look for practical markers rather than perfection. Do urges peak and pass a little more quickly. Can you name what you feel before it spikes. Are you reaching out sooner. Do you need fewer urgent steps to steady yourself. Track in a tiny log with three columns: trigger, practice used, next safe action. Review weekly to notice what works and what to adjust.

How do I involve a partner, friend, or family member without putting everything on them?

Create a micro-script you can send that signals need and names the ask, for example “Red level ten minutes. Stay on the phone while I do five-senses grounding, then help me set up tea.” Practice together when calm. Share two or three practices they can coach you through and two phrases that help, such as “You are not a burden” and “Stay with me right here.”

Is group practice safe if I have suicidal thoughts?

It can be, with structure. Choose groups that have clear facilitation, options to keep cameras off, and a way to step out quietly if you become overwhelmed. Let the facilitator know privately that you are using mindfulness for crisis support so they can offer alternatives if an exercise is too activating. Pair group sessions with individual check-ins or a brief debrief with a trusted person.

How much and how long should I practice to see benefits?

Think small and frequent. Three to five micro-practices per day, even at thirty to sixty seconds each, build a reliable reflex over a few weeks. Anchor them to existing routines such as after brushing teeth, before opening email, and when sitting down to eat. Expect uneven days. The aim is not streaks; it is skill under pressure.

What if I feel ashamed when a practice does not work?

Name the shame out loud if you can. Then shift the frame from success or failure to experimentation. Ask “What did I learn about my state and what might I try next.” Many people need two or three moves in sequence, for example cold water, then five-senses grounding, then a compassionate pause. You are training a toolkit, not proving anything.

How do I talk with my therapist about using mindfulness for suicidal urges?

Bring specifics. Share which practices felt stabilizing, which were too activating, and exactly when you used them relative to the urge. Ask to weave them into your safety plan and to rehearse one or two practices in session so you can adjust them together. If you have trauma triggers, request titrated, eyes-open versions and clear stop signals.

Can mindfulness help with urges to self-harm that are not explicitly suicidal?

Yes. The goal is similar: create space between urge and action and bring the body back within a tolerable range. Use strong sensory anchors such as holding ice, snapping a rubber band on your wrist followed by self-soothing lotion, or a brisk face rinse, then shift to a gentler practice like breath counting or the compassionate pause. Pair with your alternative-behavior list and follow with connection.

What role do personal values play alongside mindfulness in crisis moments?

Values help you choose the next right action once you have a few seconds of space. After a brief grounding practice, ask “What do I care about most that I can act on in the next five minutes.” Examples include texting a friend because you value connection, feeding a pet because you value care, or stepping outside because you value aliveness. Small value-aligned steps reinforce reasons to stay.

What should I do after a close call when I did not act on an urge?

Do a compassionate debrief within twenty-four hours. Note the early signs you missed, what helped, and one change to your plan. Mark the effort with a small ritual such as lighting a candle, stepping outside for fresh air, or writing a two-line note to your future self. Share the debrief with your therapist or a trusted person so you are not carrying it alone.

When is mindfulness not the right tool for me right now?

If you cannot ensure your immediate safety, if you are experiencing severe command hallucinations, or if inward focus reliably intensifies panic or trauma flashbacks, prioritize crisis resources, medication adjustments, or a higher level of care. You can return to short, external-focus practices later, once stabilization is in place. Safety comes first; mindfulness can wait.

Can I use mindfulness discreetly at work or in public without drawing attention?

Yes. Try silent breath counting with longer exhales, press your thumb and finger together and notice the sensation, count the corners of a room, read the exits and windows to orient, or name three objects in your mind that are the color blue. These micro-practices are invisible to others and can buy you a few minutes to choose your next step.

How do I prevent unhelpful comparisons when I see other people seem “better” at mindfulness than me?

Treat comparison as a cue to return to your own experience. Silently note “comparing” and place a hand on a neutral surface. Remember that mindfulness is not a performance; it is a personal safety skill. Your only measure is whether you gained even a sliver of space between the urge and the action.

What myths about mindfulness and suicidality should I ignore?

Myths include the idea that mindfulness means emptying your mind, that you must sit perfectly still, or that if it does not work immediately it will never work. Mindfulness is paying attention on purpose, with kindness, for a moment at a time. Movement counts, micro-doses count, and uneven progress is normal. Most importantly, mindfulness is a complement to care, not a substitute for it.

REMEMBER: If you are in immediate danger or feel unable to keep yourself safe, contact local emergency services or reach the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline right now. You deserve support, and you do not have to navigate this alone.

More Reading for Suicide Prevention:

- 10 Books to Explore During Suicide Prevention Month

- Suicide Risk During Major Life Transitions (Divorce, Retirement, Moving)

- When Words Aren’t Enough: Alternative Therapies for Suicide Prevention

- Project Semicolon: An In-Depth Look at Its Origins, Growth, and Mission

- What Project Semicolon Founder Amy Bleuel’s Death Might Teach Us About Suicide

- Understanding Suicide Bereavement: How It Differs from Other Forms of Grief and Effective Therapeutic Approaches

- The Role of Narrative Therapy in Rewriting Suicidal Stories

- Intergenerational Trauma and Its Link To Suicide in Families

- How Attachment Styles Relate to Suicidal Thinking