The stories families carry across generations often shape identity, relationships, and resilience. Yet, when trauma is left unacknowledged or unresolved, it can echo through time, influencing the mental health of future generations. The exploration of intergenerational trauma and its link to suicide in families has become a crucial area of research and clinical practice. Families who have endured war, displacement, abuse, systemic oppression, or other profound hardships may unknowingly pass down patterns of despair, silence, and self-blame. For some, these inherited burdens increase vulnerability to suicidal thoughts.

Understanding the connection between intergenerational trauma and suicide is not about assigning blame. Instead, it provides a framework for making sense of how pain is carried forward and how healing can also ripple across generations.

Find a therapist.

What Is Intergenerational Trauma?

Intergenerational trauma refers to the transmission of the emotional and psychological effects of trauma from one generation to the next. Trauma does not disappear simply because the original event is in the past. It can live on in family systems, cultural narratives, and even physiological responses. Children of trauma survivors may grow up with heightened anxiety, unresolved grief, or internalized shame without fully understanding why.

Theories of Transmission:

-

- Social Learning Theory: Children learn coping mechanisms and emotional responses by observing their parents. If a parent copes with trauma by avoiding emotions or through substance use, the child may internalize these behaviors as normal.

- Attachment Theory: Trauma can impair a parent’s ability to form secure attachments, leading to insecure attachment styles in their children. This can manifest as avoidant, anxious, or disorganized attachment, which are linked to later mental health issues.

- Epigenetics: Epigenetics suggests that environmental factors like severe stress can cause changes to our gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These epigenetic changes can then be passed down to offspring, potentially influencing their stress responses and susceptibility to conditions like PTSD. Studies on the descendants of Holocaust survivors and those who endured famine have shown evidence of such biological transmission.

Research on intergenerational trauma

Research began with Holocaust survivors and their children, but it has since expanded to include Indigenous communities, African American descendants of slavery, refugees, and families affected by widespread violence or chronic neglect. Trauma is communicated not only through stories told, but also through silence, body language, and unspoken family rules. When family members carry unprocessed trauma, it can shape parenting styles, attachment patterns, and emotional availability. This creates a cycle where pain is passed on, often unintentionally, to future generations.

The Link Between Intergenerational Trauma and Suicide

The relationship between intergenerational trauma and suicide in families is layered and complex. Children of trauma survivors may be more likely to struggle with depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress. These conditions, when combined with ongoing stressors such as discrimination or poverty, heighten suicide risk.

Elevated Risk Factors:

-

- Increased Mental Health Vulnerability: Children of parents with PTSD are more likely to develop anxiety, depression, or PTSD themselves. Studies have found that children of parents with PTSD had a significantly higher risk for suicide attempts.

- Impaired Coping Mechanisms: Families with unresolved trauma often lack healthy emotional regulation and communication skills. They may suppress emotions, leading to a build-up of unexpressed grief and anger that can contribute to feelings of hopelessness.

- Chronic Stress and Allostatic Load: Continuous exposure to stress, known as allostatic load, can lead to physiological wear and tear on the body. This is particularly true for marginalized groups who face both historical trauma and ongoing systemic oppression. The body’s “fight or flight” response can become chronically activated, leading to a breakdown in mental and physical health.

For example, a parent who endured abuse may struggle with emotional regulation. Without realizing it, they may pass down patterns of fear or detachment to their children. A family that has lived through war or genocide may emphasize silence and survival over emotional expression. The next generation may internalize a belief that their pain is unspeakable or unworthy of care. Over time, these dynamics contribute to a sense of isolation and hopelessness that increases suicidal vulnerability.

Suicide risk also rises when family trauma intersects with systemic oppression. Communities that face ongoing racism, homophobia, or economic injustice often carry compounded trauma. The combination of historical wounds and current inequities places individuals at heightened risk.

Silence, Shame, and the Family Narrative

One of the most powerful ways intergenerational trauma influences suicide risk is through silence and shame. When trauma is not discussed openly, family members may sense the presence of something unspoken, yet feel unable to name it. This silence can create confusion, self-blame, or a belief that one’s struggles are personal flaws rather than inherited wounds.

The Role of Silence:

-

- “Secrets” and the Family System: Family secrets, particularly those related to trauma, can create a palpable tension. Children may pick up on this “emotional static” without understanding its source, leading to anxiety and confusion.

- The Unspoken Rule: Many families of trauma survivors have an unspoken rule: “Don’t talk about what happened.” This is often a protective mechanism, but it can backfire by preventing the processing of painful events. It teaches younger generations that pain is something to be hidden, not healed.

Shame often becomes central to the family story. Individuals may carry a narrative that they are broken, defective, or undeserving of love. This internalized story can become overwhelming, leaving suicide to feel like an escape from unbearable self-judgment. Therapy that makes space for naming, processing, and rewriting these inherited stories is critical in disrupting this cycle.

Breaking the Cycle Through Therapy

The good news is that intergenerational trauma does not have to dictate the future. Therapy provides a way to uncover and interrupt the patterns that increase suicide risk. Several approaches have proven particularly helpful.

Key Therapeutic Approaches:

-

-

- Narrative Therapy: By externalizing trauma and reframing family stories, narrative therapy allows individuals to separate their identity from inherited pain. This approach helps clients recognize that they are more than the trauma passed down to them. The therapist helps the client co-author a new, empowering narrative.

- Trauma-Informed Care: Therapists trained in trauma awareness understand how to recognize triggers, regulate the nervous system, and create safe spaces for healing. This is particularly important for clients carrying multigenerational wounds. A trauma-informed approach prioritizes psychological safety and builds trust.

- Family Systems Therapy: Engaging multiple generations in conversation can help reveal unspoken patterns and foster healing across the family system. Breaking cycles of silence and shame is often most powerful when done collectively. This therapy recognizes that the “identified patient” is often a symptom of a larger family dynamic.

- Somatic Approaches: Trauma is not only psychological but also physiological. Practices that integrate body awareness, such as Somatic Experiencing (SE), help release trauma stored in the nervous system. The SE theory, developed by Peter Levine, posits that trauma is not just a mental event but a physiological one, and that releasing the “stuck” energy from a traumatic event is key to healing.

-

Through these and other approaches, therapy supports clients in recognizing patterns, reclaiming agency, and creating new narratives of resilience.

Protective Factors That Promote Healing

While intergenerational trauma increases suicide risk, protective factors offer hope. Families who actively process and speak about their histories often lessen the silence, shame, and isolation that accompany inherited wounds. Communities that create safe spaces for storytelling and connection serve as vital buffers, reminding individuals they are not alone in their struggle or healing.

Healing is not about erasing pain but about transforming it – reclaiming voice, identity, and connection where trauma once imposed silence and fragmentation.

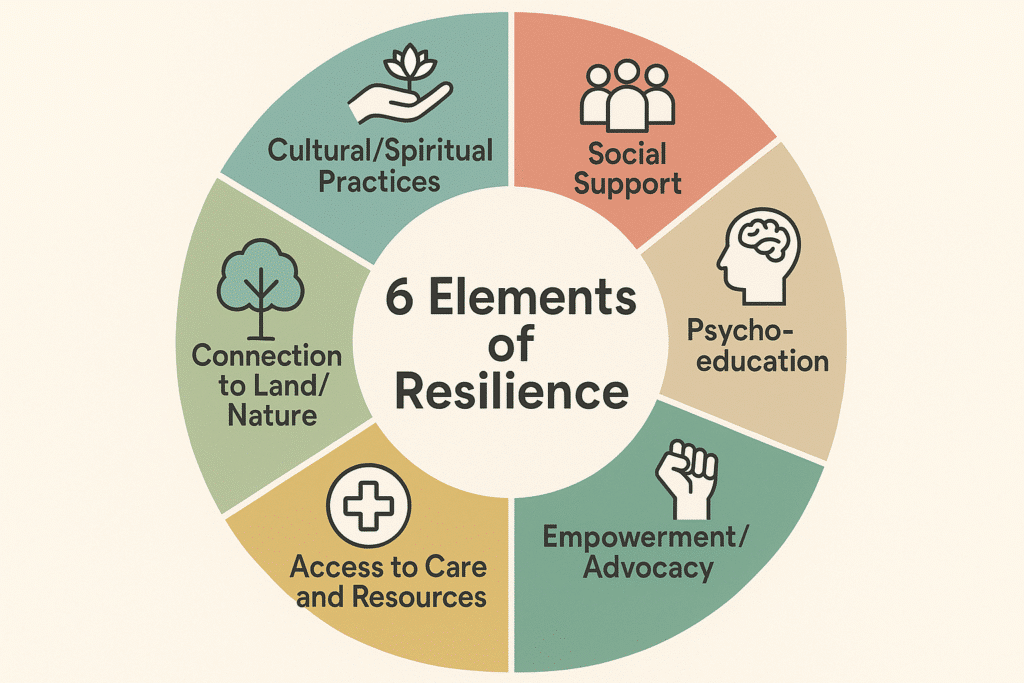

Elements of Resilience

Cultural and Spiritual Practices

-

Revitalizing language programs, storytelling, and song to reconnect younger generations with their cultural roots.

-

Community ceremonies that honor ancestors and affirm collective survival.

-

Spiritual grounding practices such as prayer, meditation, or sweat lodges that provide structure, purpose, and continuity.

Social Support

-

Mentorship programs linking youth with elders who share wisdom and survival stories.

-

Peer support circles, where people with similar histories can validate and encourage one another.

-

Extended kinship systems, where caregiving is shared across families and no one is left isolated.

Psychoeducation

-

Workshops that explain how trauma affects the brain and body, helping people understand patterns of anxiety, depression, or substance use.

-

Generational dialogues, where parents and children learn about trauma together, breaking cycles of silence.

-

Community trainings for teachers, healthcare workers, and leaders to recognize and respond to trauma-informed needs.

Access to Care and Resources

-

Availability of culturally competent mental health professionals who understand historical trauma.

-

Integration of traditional healing with modern therapeutic approaches (e.g., combining talk therapy with drumming or art therapy).

-

Access to safe housing, education, and financial stability, which reduce stressors that can worsen trauma’s impact.

Empowerment and Advocacy

-

Involvement in activism or community organizing, giving individuals a sense of agency and power over systemic oppression.

-

Youth leadership programs that nurture confidence and self-worth.

-

Storytelling projects (oral histories, books, films) that reframe communities not only as sites of suffering, but also of resilience.

Connection to Land and Nature

-

Gardening, foraging, or land-based practices that restore relationships with the earth.

-

Outdoor programs that build confidence, connection, and healing through time in natural environments.

-

Reclaiming sacred sites and using them for ceremonies, grounding individuals in ancestral homelands.

The Ongoing Journey

Protective factors do not erase trauma, but they weave threads of resilience into the fabric of life. Healing is rarely linear—it unfolds in steps, setbacks, and breakthroughs. Yet every moment of connection, every ritual reclaimed, and every conversation about pain carried across generations weakens the grip of inherited despair. Over time, these collective acts of healing transform trauma into strength, restoring not only individuals but entire communities.

Why This Matters for Suicide Prevention

Understanding intergenerational trauma and its link to suicide in families matters because it expands the frame of prevention. Suicide is not simply an individual problem. It is influenced by histories, systems, and family legacies. By addressing these broader contexts, therapists and communities can create more effective pathways to healing.

When families recognize that their pain has roots in collective history, individuals often feel relief. Their struggles are no longer seen as personal failings but as survivable echoes of past suffering. Therapy then becomes a process not only of survival but of transformation—rewriting the story for the next generation.

Many of our therapists work with people who are interested in understanding and moving forward from generational trauma. Browse our therapist directory to find a therapist today.

More Reading for Suicide Prevention:

- 10 Books to Explore During Suicide Prevention Month

- Suicide Risk During Major Life Transitions (Divorce, Retirement, Moving)

- When Words Aren’t Enough: Alternative Therapies for Suicide Prevention

- Project Semicolon: An In-Depth Look at Its Origins, Growth, and Mission

- What Project Semicolon Founder Amy Bleuel’s Death Might Teach Us About Suicide

- Understanding Suicide Bereavement: How It Differs from Other Forms of Grief and Effective Therapeutic Approaches

- The Role of Narrative Therapy in Rewriting Suicidal Stories