Attachment is one of the most powerful forces in human development. From birth onward, the way we bond with caregivers shapes how we see ourselves, how we connect with others, and how we respond to distress. For many, attachment provides security and resilience. For others, it creates vulnerabilities that can echo across a lifetime.

In recent decades, therapists and researchers have increasingly explored how attachment patterns influence suicidal thinking. While no single factor “causes” suicidal ideation, insecure or disrupted attachment styles shape the ways people experience pain, seek support, and construct meaning. Understanding these dynamics can reduce stigma, identify risk factors, and open pathways toward healing.

Find a Therapist

A Primer on Attachment Theory

Attachment theory, first introduced by John Bowlby and expanded by Mary Ainsworth, describes how early caregiving experiences create internal “working models” of self and others. These models determine whether people believe they are lovable and whether others can be trusted to respond to their needs.

The four primary attachment styles offer a useful framework.

- Secure attachment develops when caregivers are responsive and consistent. Individuals usually trust others, regulate emotions well, and build healthy relationships.

- Anxious attachment arises when caregiving is inconsistent. People often fear abandonment, crave closeness, and struggle with self-worth.

- Avoidant attachment emerges when caregivers are emotionally unavailable or dismissive. These individuals may value independence but find intimacy difficult.

- Disorganized attachment typically results from neglect, abuse, or frightening caregiving. It blends anxious and avoidant tendencies and is strongly linked with unresolved trauma.

These patterns are not fixed destinies but strategies. They help children survive their early environments, but they can also leave lasting vulnerabilities when distress feels overwhelming.

Suicidal Thinking as an Attachment Wound

Suicidal thoughts can be understood as more than individual despair; they often reflect relational wounds. Bowlby described the progression from protest to despair to detachment when bonds are threatened. Suicidal ideation frequently emerges when detachment takes hold and the person concludes that reconnection is impossible and life without belonging is unbearable.

For those with anxious attachment, the fear of abandonment can make everyday conflicts feel catastrophic. When efforts to gain reassurance fail, despair deepens. Suicidal thoughts may emerge as both a protest, calling attention to pain, and as an expression of hopelessness, suggesting that survival without connection is unthinkable.

For those with avoidant attachment, the danger lies in suppression. These individuals minimize needs and emotions to protect themselves, but when pain has no outlet and seeking help feels unsafe, thoughts of escape through death can intensify. Their suicidal ideation may remain hidden, which increases risk.

For those with disorganized attachment, the situation is often most perilous. Early caregiving that was both a source of comfort and terror leaves the nervous system fragmented. The longing for closeness collides with the fear of it, creating unbearable inner conflict. Suicidal thoughts can appear as the only imagined way to escape this paradox.

Researchers Expand on These Insights

Several leading theorists have provided frameworks that help explain the overlap between attachment and suicidality. Edwin Shneidman described suicide as an attempt to end what he called psychache, the unbearable psychological pain that arises when core needs for belonging, safety, and meaning are frustrated. His work reminds us that suicide is not about the wish for death itself but about the desire to escape a pain that feels intolerable.

Thomas Joiner offered a complementary perspective through the interpersonal theory of suicide. He argued that suicidal desire develops when people experience two states simultaneously: perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. In other words, when someone feels they are a liability to others and simultaneously cut off from meaningful connection, the conditions for suicidal ideation deepen. These themes appear often in insecure and disorganized attachment patterns, where rejection and shame are internalized as enduring truths.

Peter Fonagy and Anthony Bateman contributed another critical layer with their work on mentalization. They observed that under attachment stress, the ability to see oneself and others as having complex inner lives can collapse. When mentalization fails, individuals can no longer imagine that others might care or respond with empathy. They become convinced that no one can understand or help. This collapse intensifies the sense of isolation that fuels suicidal thinking.

Taken together, these theories demonstrate that suicidal ideation is rarely just a matter of mood or brain chemistry. It is often an attachment wound, a crisis of connection, meaning, and worth. Understanding this helps therapists and families move away from purely symptom-focused approaches and toward interventions that restore relationships and rebuild a sense of belonging.

Embodied Attachment and Suicide Risk

Attachment does not live only in the mind or in abstract relational patterns. It is also written into the body. Our nervous systems are shaped by early caregiving, and they carry forward those patterns into adulthood. When attachment wounds are activated, the body often responds before the mind fully registers what is happening. This is why suicidal thoughts are frequently experienced not just as ideas but as overwhelming sensations: racing hearts, numbness, collapsing energy, or unbearable tension.

For people with anxious attachment,

the body may signal danger through hyperarousal. A racing heart, rapid breathing, and stomach pain can accompany the fear of rejection. When reassurance does not come, these bodily alarms can feel unbearable, and suicidal ideation may emerge as a desperate attempt to stop the unrelenting activation.

For people with avoidant attachment,

the body often shifts in the opposite direction. Emotions are numbed, muscles lose tension, and a sense of disconnection from one’s own physical state can dominate. This shutdown, while protective in the moment, can create an emptiness that feeds hopelessness. Suicidal thoughts may appear here as a way of resolving the feeling that one is both untouchable and unreachable.

For people with disorganized attachment,

the nervous system can oscillate between extremes. At times it surges into hyperarousal, at other times it collapses into numbness. This push and pull can create a sense of being trapped in a body that cannot find safety. Suicidal thinking can seem like the only escape from this biological storm.

Therapy that integrates the body can be especially powerful in these moments. Polyvagal-informed approaches and other somatic practices help clients notice and regulate bodily states. Grounding exercises, mindful breathing, safe touch, or movement can interrupt cycles of panic and shutdown. Over time, clients learn that their bodies are not only sites of alarm but also resources for calm, connection, and vitality.

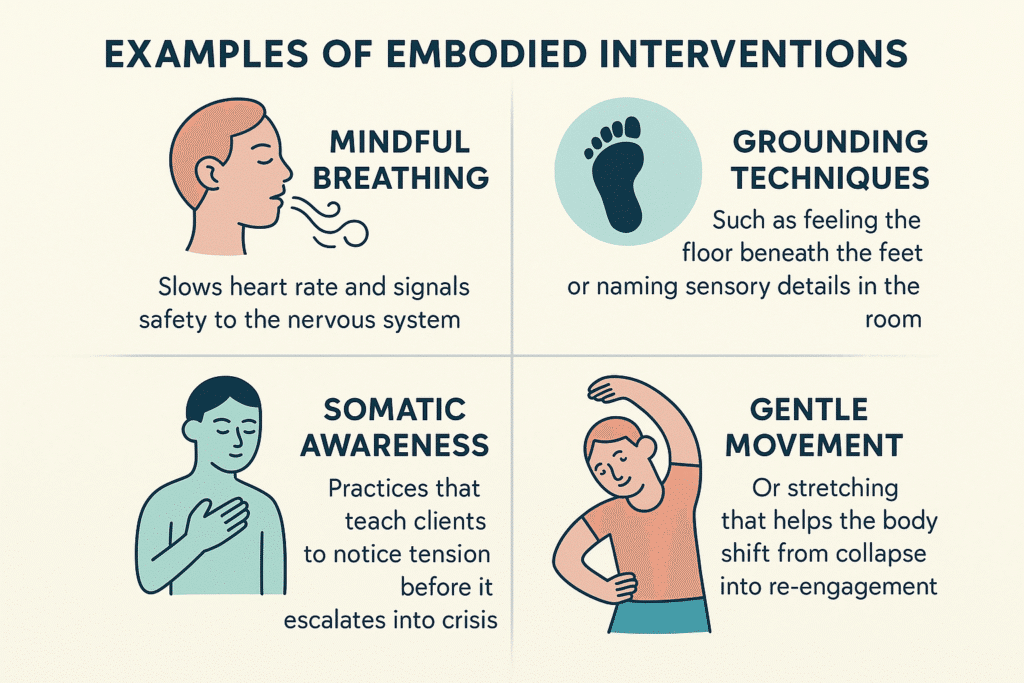

Examples of embodied interventions include:

-

Mindful breathing that slows heart rate and signals safety to the nervous system

-

Grounding techniques such as feeling the floor beneath the feet or naming sensory details in the room

-

Somatic awareness practices that teach clients to notice tension before it escalates into crisis

-

Gentle movement or stretching that helps the body shift from collapse into re-engagement

By restoring a sense of bodily safety, these practices make it easier to challenge the thoughts that drive suicidal despair. Clients discover that relief can come not only from others’ responses but also from within their own nervous system. This embodied perspective adds another layer to understanding attachment and suicide, showing that healing happens not just in the mind or the relationship but also in the felt experience of the body.

What Happens in Therapy for Attachment-Related Suicidality

Therapy provides more than a place to talk. It becomes a corrective relational experience, offering what was often missing in early caregiving: consistency, attunement, and repair. Unlike ordinary relationships, therapy is designed to hold distress safely and intentionally.

Early phases often focus on mapping patterns. A therapist helps the client identify how attachment strategies such as pursuing, withdrawing, or freezing show up during crises. For example, an anxious client might learn to recognize the sequence: partner does not respond, panic sets in, catastrophic beliefs emerge, and a suicidal spiral follows. Making these links visible reduces chaos and fosters agency.

As trust grows, therapy deepens. Mentalization-Based Therapy helps clients stay curious about their own and others’ minds, reducing black-and-white thinking. Dialectical Behavior Therapy teaches skills for tolerating distress and regulating intense emotions. Attachment-Based Family Therapy facilitates conversations where parents and youth repair ruptures, offering direct experiences of responsiveness. Emotionally Focused Therapy helps couples and families restructure interaction patterns to provide security rather than distance. Trauma-focused approaches like EMDR reprocess painful memories that drive disorganized attachment.

Perhaps most importantly, therapy models rupture and repair. When misunderstandings arise, the therapist names them and works through them, demonstrating that conflict does not have to end in abandonment. This experience contradicts what many clients learned in childhood, where ruptures meant withdrawal or punishment. Over time, clients internalize these corrective experiences, building a sturdier sense of self and a capacity to seek help when suicidal thoughts arise.

The Role of Relationships Outside Therapy

Friends, partners, families, and communities play an essential role in recovery. They provide everyday belonging, affirmation, and shared life that therapy alone cannot offer. A supportive partner who checks in regularly, a friend who listens without judgment, or a community group that welcomes participation all buffer against despair.

Yet these relationships are not designed to carry the full weight of suicidal pain. Loved ones can feel overwhelmed, uncertain, or reactive. Therapy differs in that it is boundaried, consistent, and intentionally focused on healing. Its purpose is not to replace other relationships but to prepare clients to participate in them more securely. Therapy equips clients with language for needs, tools for regulation, and scripts for reaching out, making other relationships more supportive and less fraught.

Beyond Attachment: Other Frameworks That Add Insight

While attachment provides a powerful lens, other theories enrich our understanding.

- The interpersonal theory of suicide emphasizes how belongingness and burdensomeness combine to create risk.

- Rory O’Connor’s Integrated Motivational Volitional model highlights defeat and entrapment as key drivers.

- Polyvagal theory shows how the nervous system shifts from connection to fight or flight and eventually to shutdown under threat, shaping how suicidal crises feel in the body.

- Cultural perspectives also matter, reminding us that histories of colonization, racism, displacement, and community trauma shape attachment and suicide risk. Healing in these contexts often requires cultural reconnection, rituals, and collective belonging.

Together, these frameworks highlight that suicidality is never just an individual problem. It emerges from disrupted relationships, meanings, and social contexts, and it can be healed within them.

FAQ About Attachment and Suicide

Does insecure attachment mean I will develop suicidal thoughts?

Not necessarily. Insecure attachment increases vulnerability but does not guarantee suicidality. It interacts with life stressors, mental health conditions, and available supports. Many people with insecure attachment never experience suicidal ideation, especially if they have protective factors like strong friendships, cultural identity, or access to therapy.

Can attachment patterns change?

Yes. Researchers speak of earned security, the process of moving from insecurity to security through repeated corrective experiences. Therapy offers opportunities to risk vulnerability, receive responsiveness, and survive ruptures without abandonment. Over time, these experiences update the nervous system, teaching that closeness is survivable and needs are acceptable.

Why do rejections or breakups trigger suicidal spirals?

Attachment systems are activated by threats to connection. For an anxious person, rejection may confirm the fear that they are unlovable. For an avoidant person, it may reinforce the belief that closeness is unsafe and that they are on their own. Disorganized attachment often makes such losses feel both urgently needed and unbearably threatening. Therapy helps by slowing down this process, teaching regulation skills, and reframing rejection as painful but survivable rather than catastrophic.

What makes therapy different from talking with friends?

Friends and family are vital for belonging, but they cannot consistently contain the intensity of suicidal despair. Therapy differs in its structure: it is predictable, confidential, and one-sided, with a professional trained to hold, name, and work through rupture. The goal of therapy is to prepare clients to engage more securely in personal relationships, so that those bonds can provide support without becoming overwhelmed.

Which therapies are most effective for attachment-related suicidality?

Several modalities are particularly effective. Mentalization-Based Therapy restores the ability to understand minds under stress. Dialectical Behavior Therapy reduces self-harm and suicide attempts through skills. Attachment-Based Family Therapy repairs parent–child bonds in adolescents and young adults. Emotionally Focused Therapy strengthens bonds in couples and families. EMDR and other trauma therapies reprocess painful attachment memories. What matters most is that the therapy explicitly attends to attachment and creates a space for safety, repair, and growth.

How can loved ones help in the moment?

The most powerful interventions are simple: convey belonging by affirming “You matter to me,” reduce shame by saying “You are not a burden,” and remain present even in silence. Practical steps such as sitting together, helping the person use coping strategies, or contacting supports are often more effective than arguments or forced positivity. Families can prepare by developing safety plans together that include clear roles, scripts, and resources.

From Wounds to Connection

Suicidal thinking often reflects not a wish to die but a wish for unbearable pain to end, pain rooted in ruptured or absent connections. Attachment theory helps us see that these thoughts are not merely symptoms to manage but relational wounds that can be understood and healed.

Therapy offers one pathway toward this healing. By providing a consistent, attuned relationship, it helps clients rewrite old narratives, regulate overwhelming emotions, and risk connection again. Communities and loved ones extend this work by offering everyday belonging. Healing is not linear, but it is possible.

Our therapists can help. They work with clients to explore attachment wounds, reduce suicidal pain, and build life-affirming patterns of connection.

More Reading for Suicide Prevention:

- 10 Books to Explore During Suicide Prevention Month

- Suicide Risk During Major Life Transitions (Divorce, Retirement, Moving)

- When Words Aren’t Enough: Alternative Therapies for Suicide Prevention

- Project Semicolon: An In-Depth Look at Its Origins, Growth, and Mission

- What Project Semicolon Founder Amy Bleuel’s Death Might Teach Us About Suicide

- Understanding Suicide Bereavement: How It Differs from Other Forms of Grief and Effective Therapeutic Approaches

- The Role of Narrative Therapy in Rewriting Suicidal Stories

- Intergenerational Trauma and Its Link To Suicide in Families