Suicidal thoughts often feel like an internal battle. One part of us longs to live, while another insists that giving up is the only way forward. For many, this struggle can feel shameful and isolating, as though the very existence of suicidal thoughts means something is deeply wrong. Internal Family Systems (IFS) offers a compassionate alternative. It reframes suicidal ideation as the voice of a part, not the whole person, and invites us to meet even the darkest inner voices with curiosity rather than judgment.

IFS provides a framework for healing that honors every voice within us, even the ones that feel unbearable. It is not a substitute for crisis intervention, and anyone in immediate danger should seek urgent help. However, for those who want to understand and transform the roots of suicidal despair, IFS opens a pathway that is both hopeful and deeply human.

The Basics of Internal Family Systems

IFS is a therapeutic model developed by Dr. Richard Schwartz. It is built on the idea that the mind is not a single, unified entity but rather a system of parts, each with its own feelings, perspectives, and intentions.

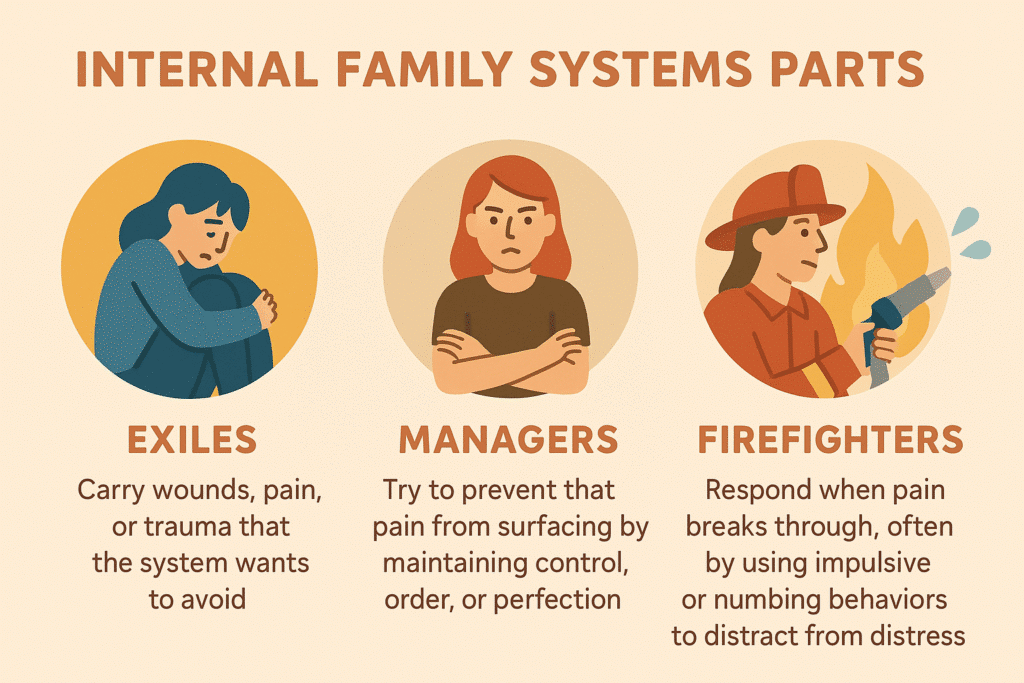

According to IFS, every person has:

-

Exiles, which carry wounds, pain, or trauma that the system wants to avoid

-

Managers, which try to prevent that pain from surfacing by maintaining control, order, or perfection

-

Firefighters, which respond when pain breaks through, often by using impulsive or numbing behaviors to distract from distress

At the core of the system is the Self, which represents our innate wisdom, compassion, and capacity to lead our internal system with calmness and care. Healing comes not by silencing or destroying parts, but by listening to them and helping them trust the leadership of the Self.

Find a Therapist

Suicidal Thoughts as a Part of the System

In IFS, suicidal thoughts are understood as one part of the internal system rather than as the entirety of who someone is. This perspective is transformative because it shifts suicidal ideation from being seen as the essence of a person to being just one voice among many.

Often, the suicidal part emerges as a protector. Its purpose, however misguided, is to shield the person from unbearable emotional pain. For instance, if an exile carries overwhelming shame, grief, or a sense of worthlessness, the suicidal part may believe that ending life is the only way to bring relief. When understood this way, suicidal thoughts are not random or meaningless. They carry an intention to protect, even though the strategy they choose is harmful.

It is also important to recognize that suicidal parts rarely exist in isolation. They are often linked to other roles within the system. Managers may have pushed the person toward perfection or self-control for years. Firefighters may have tried to soothe the pain through numbing or impulsive behaviors. When these strategies stop working, the suicidal part may step in as a last resort. Understanding this interplay helps make sense of why suicidal despair feels so overwhelming: it is the voice of a system exhausted by years of managing pain.

The Role of Managers and Firefighters

The parts of us that want to give up are rarely acting alone. They often emerge when managers and firefighters have exhausted their strategies. Managers push for control, perfection, or constant achievement. They operate under the belief that if everything is kept in order, pain will never surface. Firefighters, on the other hand, leap into action when pain breaks through. They may numb emotions with alcohol, drugs, overwork, overeating, or withdrawal.

When these strategies fail, the suicidal part may rise as a desperate measure. For example, a manager may insist on perfection at work. When a mistake happens, shame floods the system. A firefighter might try to soothe with alcohol, but if that numbing no longer works, the suicidal part may appear and declare that ending life is the only escape.

Mapping these internal interactions helps people see that their suicidal thoughts are not isolated or random. They are part of a system that has been trying, often heroically, to manage unbearable pain. This recognition fosters compassion for the self and makes room for new, healthier strategies to emerge.

The Power of the Self

Central to IFS is the belief that every person has a Self that is capable of healing. The Self is calm, compassionate, curious, and courageous. It is not destroyed by trauma, despair, or suicidal thoughts, although it can be obscured by the intensity of parts in pain.

When the Self is able to connect with suicidal parts, it can ask important questions: What are you trying to protect me from? What do you need me to know? How can I help you find another way? This internal dialogue reframes suicidal thoughts as signals pointing toward unresolved wounds rather than as final verdicts.

The Self becomes a source of leadership. Instead of managers and firefighters working frantically to protect against exiles, the Self helps the entire system reorganize. Suicidal parts, once seen as dangerous, may learn to trust the Self and step back from their extreme roles. Healing in IFS is not about erasing parts but about helping each one find a healthier role under the guidance of the Self.

Why This Matters for Suicidal Ideation

Internal Family Systems matters because it shifts how we understand suicidal thoughts. Instead of seeing them as something to suppress, IFS views them as parts trying to help in the only way they know. This does not mean agreeing with suicidal thoughts, but it does mean listening to what they are protecting and what needs they are expressing.

By bringing compassion to suicidal parts, many people discover that what these parts truly want is relief, rest, or freedom from shame. Therapy then focuses on meeting those needs in ways that do not involve self-harm. This reframing reduces shame, fosters inner harmony, and creates space for hope.

Healing Through IFS

IFS sessions often involve guided inner dialogues. A therapist may help someone visualize or sense the suicidal part and begin a conversation. Instead of pushing the part away, the goal is to approach it with curiosity and compassion. Over time, these parts begin to trust the Self, releasing their extreme roles as protectors.

For example, a suicidal part that believes death is the only escape from shame may soften when it realizes that the Self and other supportive parts can offer compassion, connection, and safety. As trust grows, the burden carried by that part can be released. This process reduces suicidal ideation and restores hope.

Practical Tools in IFS Work

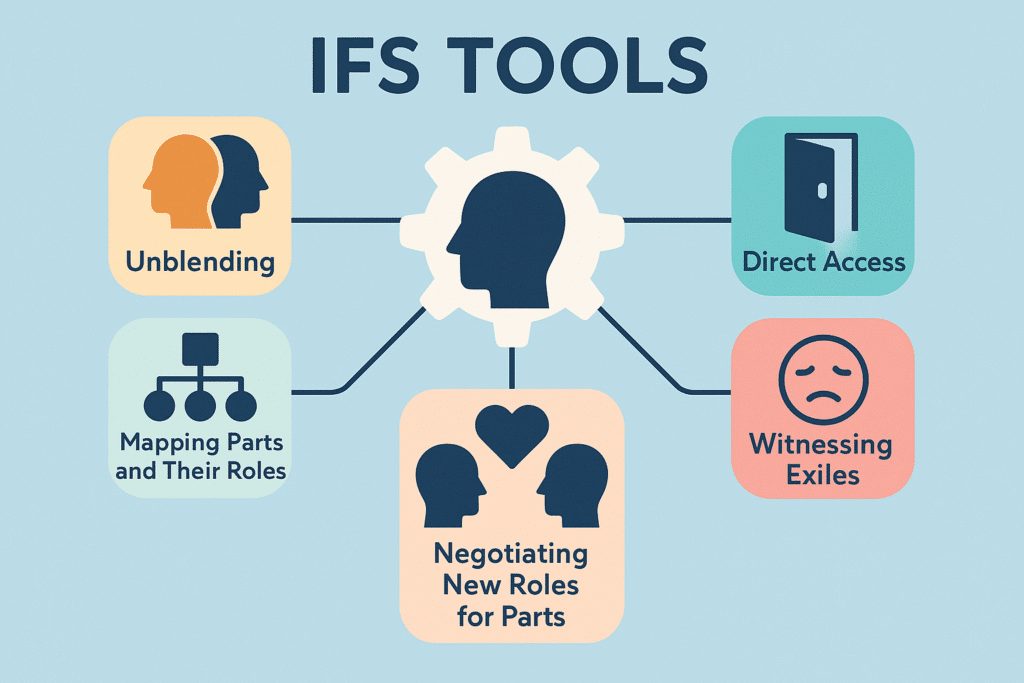

Unblending

Unblending means separating from the suicidal part enough to notice that it is only one part of the self, not the whole identity. For example, instead of saying “I want to die,” a person might begin to say, “A part of me feels like giving up.” This shift reduces the intensity of suicidal thoughts and opens space for the Self to step in with curiosity and compassion.

Direct Access

Direct access involves speaking directly to the suicidal part. Someone might ask: “What are you afraid would happen if you were not here?” or “What are you trying to protect me from?” This practice gives the part a voice and helps uncover the deeper wounds or fears that fuel its presence.

Witnessing Exiles

Suicidal parts are often protecting exiles that hold pain from past experiences. Witnessing allows these exiled parts to finally be seen and validated. For example, an exile carrying childhood shame may be given space to express its story. When exiles feel heard, their intensity decreases, which in turn softens the suicidal protector.

Self-to-Part Dialogue

This practice fosters direct communication between the Self and the suicidal part. The Self might say, “I see how hard you have been working to protect me” or “I want to help you find a safer way to take care of me.” Over time, this dialogue builds trust, and the suicidal part learns it does not have to carry its extreme role alone.

Mapping the System

Therapists often help clients map out their parts, showing how managers, firefighters, exiles, and suicidal protectors interact. Seeing this map helps people understand why suicidal thoughts surface and provides a roadmap for healing.

Developing New Roles

IFS does not seek to eliminate parts, but to help them adopt healthier roles. A suicidal part might transform into a fierce advocate for rest, boundaries, or self-care once it trusts that the Self and other parts can meet the system’s needs.

Why IFS Offers Hope

What makes IFS uniquely hopeful is its foundational belief: there are no bad parts. Even the suicidal part is not an enemy. It is a protector doing its best under impossible circumstances. By recognizing its intention, people reduce internal conflict and begin to build harmony within.

For individuals struggling with suicidal ideation, this message is transformative. It means their thoughts do not define them. It means that healing is possible, because even the darkest parts can be understood and helped.

Moving Forward

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, immediate support is available through the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. For ongoing healing, Internal Family Systems provides a unique framework for listening to and transforming the parts of us that want to give up.

At our practice, some of our associate therapists integrate IFS into their work. We invite you to browse our therapist directory and connect with a provider who can help you explore your inner system with compassion and care.

Find a Therapist

FAQ: Internal Family Systems and Suicidal Ideation

What if my suicidal part does not trust the Self?

It is very common for suicidal parts to resist trusting the Self. Many of these parts have been carrying protective duties for years, sometimes decades, and they may believe they are the only thing keeping the person safe from unbearable emotional pain. They may also doubt that the Self even exists or can be strong enough to help.

In IFS, trust is not demanded but built slowly. A therapist will often help you first acknowledge the suicidal part’s fears and respect the intensity of its role. Instead of trying to silence or override it, the Self can approach it with curiosity: “I hear how much you have been protecting me. I want to understand what it has been like for you.” Over time, this dialogue begins to soften the part’s rigid stance. Healing in IFS is not about pushing parts into submission but about cultivating trust through repeated experiences of being heard and cared for.

Can listening to suicidal parts make urges stronger?

At first glance, some worry that turning attention toward suicidal parts might validate them or intensify suicidal urges. In practice, the opposite usually happens. When suicidal parts are ignored, shamed, or fought against, they often grow louder in an effort to be noticed. By contrast, when the Self listens with compassion, the suicidal part feels acknowledged and does not have to escalate as forcefully.

For example, a suicidal part that says, “You should end this now,” might actually be trying to stop the crushing feelings of worthlessness carried by an exile. Once the Self listens to its protective intent, the suicidal part can begin to relax, especially when it realizes there are new strategies available for easing suffering. Therapists also balance this exploration with careful safety planning, so that listening to suicidal parts remains grounding rather than overwhelming.

How does IFS handle crisis situations?

IFS is not a replacement for crisis intervention. If you or someone you love is in immediate danger of acting on suicidal urges, external supports such as the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline or hospitalization may be necessary. Crisis situations require stabilization first, because in that moment, the nervous system is overwhelmed and not able to engage in reflective inner work.

Once safety is established, IFS becomes highly effective for understanding what led to the crisis. The suicidal part can be approached with compassion and asked what it was trying to protect the system from. Clients often discover that these parts are not destructive enemies but exhausted protectors that felt out of options. In this way, IFS helps transform future crises by addressing the root causes of despair rather than only managing surface symptoms.

Is IFS evidence-based for suicidal ideation?

Research on IFS is growing, and while direct studies on suicidality are still limited, existing evidence is promising. Clinical trials have shown that IFS reduces symptoms of PTSD, depression, and complex trauma, all of which are major predictors of suicidal ideation. Therapists working in the field also report that clients who practice IFS often experience significant relief once their suicidal parts are heard and supported.

Beyond research, IFS aligns with established understandings of suicidality. For instance, Joiner’s interpersonal theory highlights the role of burdensomeness and disconnection, both of which can be understood as exiles carrying shame or rejection. By addressing these wounded parts directly, IFS offers a mechanism for reducing the risk factors that research has identified.

How long does it take to see results with IFS?

The timeline for progress depends on the individual and the complexity of their internal system. Some people feel a sense of relief early, simply from realizing that suicidal thoughts are a part of them rather than the entirety of who they are. For others, especially those with histories of chronic trauma, it may take months or longer to build trust with suicidal parts and create sustainable change.

What is unique about IFS is that progress does not require eliminating suicidal thoughts immediately. Even small steps, such as learning to unblend from a suicidal part for a few moments, can feel transformative. Over time, as more parts experience the compassion of the Self, the intensity and frequency of suicidal urges often decrease. Healing is not quick, but it is profound and lasting.

Do all suicidal parts want the same thing?

No. One of the key insights of IFS is that suicidal parts, like all parts, have specific roles and intentions. Some suicidal parts may want to end relentless shame, others may want rest from exhaustion, and still others may hope to signal how much pain the system is in. By asking each part what it fears and what it hopes to achieve, therapy uncovers the diversity of motivations hidden within suicidal ideation.

For example, one person might discover that a suicidal part wants to escape from the pressure of perfectionistic managers, while another realizes their suicidal part is trying to stop the pain of childhood abandonment carried by exiles. Recognizing these unique motivations helps therapy offer alternatives: rest, care, and compassion that meet the needs without resorting to self-destruction.

What if I feel too blended with my suicidal part to separate from it?

Blending happens when the voice of a part feels like the entire identity. When blended with a suicidal part, a person may feel as though they are nothing but despair and that death is the only answer. This can be terrifying, and it is one of the reasons professional support is so important.

In therapy, unblending techniques help create space between the Self and the part. This might involve grounding exercises, visualization of the part as separate, or calling on other parts of the system that can act as allies. Over time, people learn that they can observe the suicidal part rather than be consumed by it. This shift often brings enormous relief, because it restores the possibility of choice.

Can family members or loved ones understand IFS when supporting someone suicidal?

Yes. While family members are not expected to conduct IFS therapy, understanding the basic idea of “parts” can transform how they respond to suicidal statements. Instead of reacting with fear or judgment, loved ones can learn to say, “I hear that a part of you feels like giving up. I also know that other parts of you want to survive, and I want to support those parts too.”

This perspective reduces shame and increases compassion. It helps families see suicidal ideation not as the whole person but as one part trying to cope with pain. For many individuals, being met with this kind of compassionate language from loved ones can reinforce the inner healing process that is happening in therapy.

CALL 988 for Immediate Crisis Support

More Reading for Suicide Prevention:

- 10 Books to Explore During Suicide Prevention Month

- Suicide Risk During Major Life Transitions (Divorce, Retirement, Moving)

- When Words Aren’t Enough: Alternative Therapies for Suicide Prevention

- Project Semicolon: An In-Depth Look at Its Origins, Growth, and Mission

- What Project Semicolon Founder Amy Bleuel’s Death Might Teach Us About Suicide

- Understanding Suicide Bereavement: How It Differs from Other Forms of Grief and Effective Therapeutic Approaches

- The Role of Narrative Therapy in Rewriting Suicidal Stories

- Intergenerational Trauma and Its Link To Suicide in Families

- How Attachment Styles Relate to Suicidal Thinking

- 12 Mindfulness Practices for Interrupting Suicidal Thinking

- The Role of Perfectionism and People-Pleasing in Suicidal Ideation

- How Somatic Experiencing Helps Heal Suicidal Despair