When someone is living with suicidal thoughts, the pain often runs deeper than daily stressors or surface-level struggles. At the heart of suicidality there is often a profound crisis of meaning. People may feel cut off from purpose, from belonging, or from a sense of connection to something larger than themselves. Transpersonal psychology offers a way to reframe despair not only as an individual problem but as a spiritual and existential struggle. By integrating psychology with spirituality and human potential, transpersonal approaches invite clients to explore dimensions of identity, purpose, and connection that traditional methods sometimes overlook.

Find a Therapist

What Is Transpersonal Psychology?

Transpersonal psychology emerged in the late 1960s as a “fourth force” in psychology, following psychoanalysis, behaviorism, and humanistic psychology. The word “transpersonal” refers to experiences that transcend the individual self and connect to larger realities, whether through spirituality, creativity, altered states of consciousness, or a sense of unity with nature and humanity.

This field emphasizes wholeness. It acknowledges that suffering and crisis are part of the human journey but also recognizes the capacity for transformation, growth, and expanded awareness. In the context of suicidality, transpersonal psychology provides a framework for understanding despair not only as a symptom of mental illness but also as a potential catalyst for deep existential exploration.

Key figures laid the groundwork for this approach. Abraham Maslow explored peak experiences and self-actualization, suggesting that human beings seek transcendence as well as survival. Stanislav Grof studied altered states of consciousness and their potential for healing trauma, developing practices such as holotropic breathwork. Viktor Frankl, though not a transpersonal psychologist by label, demonstrated in his work on logotherapy that meaning is essential for survival, even in the face of unimaginable suffering. Together, these thinkers broadened psychology beyond pathology, situating spirituality, meaning, and transcendence at the heart of healing.

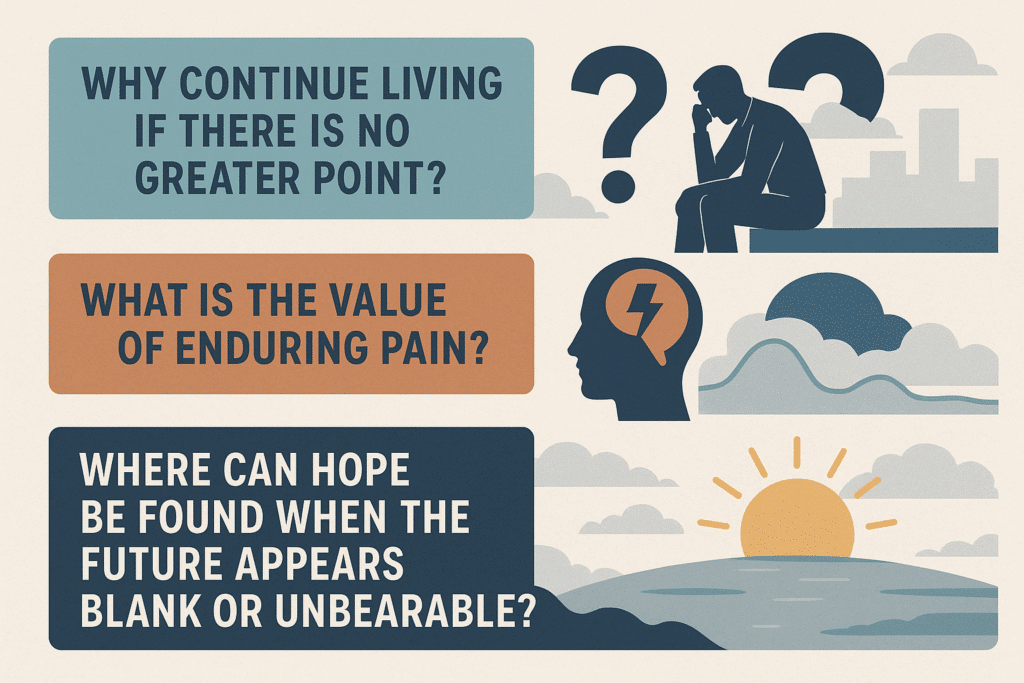

Suicidality as a Crisis of Meaning

For many people, suicidal thoughts do not arise solely from clinical depression, trauma, or chemical imbalance. They often stem from a profound sense of meaninglessness. Daily life may feel empty or devoid of purpose, leaving individuals with haunting questions. Why continue living if there is no greater point? What is the value of enduring pain? Where can hope be found when the future appears blank or unbearable? These are not casual reflections but urgent existential dilemmas that strike at the very foundation of being.

Psychologists such as Viktor Frankl argued that the will to meaning is as central to human life as the drive for survival. When this will is frustrated, despair takes hold. Suicidality can therefore be understood as a collapse of meaning-making systems. A person may no longer be able to connect their suffering to a broader story, a higher purpose, or a reason to endure. In this sense, suicidal thinking is not only a psychological symptom but an existential alarm bell signaling that the structures of purpose and connection have broken down.

Transpersonal psychology treats these questions not as weaknesses or irrational distortions but as deeply human inquiries. The very fact that someone is wrestling with the meaning of existence reveals a capacity for reflection and depth. Rather than pathologizing such questioning, transpersonal approaches invite exploration. What does it mean to be alive? Where might connection to the sacred, the creative, or the communal be rediscovered? How might suffering itself carry symbolic or transformative significance?

This reframing opens a path of possibility. Suicidal despair can be seen not only as a threat but also as a threshold. In myth, literature, and spiritual traditions, periods of darkness and disorientation often precede renewal. When clients are supported with compassion, their despair may become the starting point for transformation, a turning point where old narratives dissolve and new meanings can emerge. Therapy in this context is not about silencing existential questions but about walking with them, holding the pain while searching together for light on the other side.

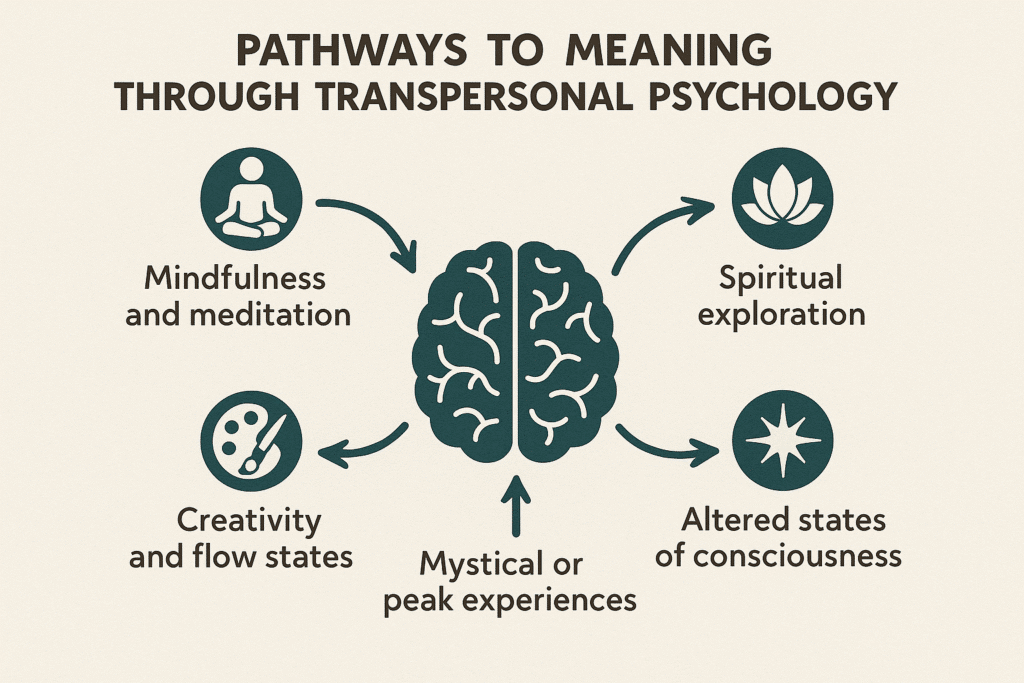

Pathways to Meaning Through Transpersonal Psychology

Transpersonal psychology offers a variety of practices and frameworks that help individuals find meaning beyond suicidality. These pathways are not quick fixes but long-term processes of reconnecting with purpose and belonging.

- Mindfulness and meditation. By cultivating presence, individuals can learn to witness their thoughts without being consumed by them. Research shows that mindfulness reduces suicidal rumination by creating space between the observing self and the stream of despairing thoughts.

- Spiritual exploration. Clients may be invited to explore spiritual traditions, rituals, or practices that provide a sense of connection to something larger. This may include prayer, contemplative practices, or immersion in nature. For Indigenous and culturally rooted communities, reconnecting to ancestral practices and rituals often provides a sense of belonging and continuity that directly counters despair.

- Creativity and flow states. Art, music, movement, and other creative practices connect individuals with transcendent experiences when words fall short. A client who paints or writes may find that these practices create a sense of flow, offering moments of freedom from despair and glimpses of hope.

- Altered states of consciousness. Some practitioners integrate safe and guided exploration of nonordinary states, such as through breathwork or, in certain therapeutic contexts, psychedelic-assisted therapy. These experiences can foster profound insights into meaning and belonging, but they must be carefully held within ethical and supportive frameworks.

- Integration of mystical or peak experiences. Many people report transformative experiences that shift their relationship with despair, such as moments of awe in nature, dreams, or sudden insights. Therapy can help clients integrate these experiences into daily life so that they become sources of resilience rather than fleeting memories.

The Role of the Therapist in Transpersonal Work

Therapists practicing from a transpersonal perspective adopt a holistic and compassionate stance. They recognize that clients are more than their struggles and that even suicidality can hold meaning as part of a larger journey. Their role is to create a safe, nonjudgmental space where spiritual and existential experiences can be explored without fear of dismissal.

A transpersonal therapist may invite exploration of values, symbols, and dreams, encourage practices that foster connection with community, nature, or spirituality, and frame crises as potential turning points for growth rather than as endpoints. They balance this openness with clear attention to safety, recognizing the real danger of suicidal crises and working with established protocols for stabilization and crisis intervention.

Importantly, transpersonal therapists help clients differentiate between spiritual bypassing and genuine transformation. Spiritual bypassing occurs when people use spiritual ideas to avoid painful realities, for example telling themselves their suffering is an illusion rather than addressing it. Effective transpersonal work requires moving through pain, not around it, and therapists model how to hold both suffering and transcendence in the same space.

But What Happens in Transpersonal Therapy?

In practice, sessions may involve:

-

Guiding mindfulness or meditation exercises that help clients witness suicidal thoughts without being consumed by them

-

Exploring symbols, archetypes, and dreams as pathways into unconscious material that may hold insight into despair and meaning

-

Encouraging creative expression such as art, journaling, or movement to externalize pain and reconnect with flow states

-

Inviting spiritual or nature-based practices that help clients feel part of something larger, whether through ritual, prayer, or time outdoors

-

Supporting integration of mystical or peak experiences into daily life so they become stabilizing resources rather than fleeting moments

-

Facilitating conversations about values, legacy, and life purpose, reframing crises as potential openings for self-discovery

-

Teaching grounding and self-regulation practices that draw from both spiritual traditions and contemporary psychology to maintain safety during moments of acute distress

These practices are not rigid techniques but flexible tools tailored to the client’s worldview, cultural background, and needs. The therapist’s presence itself becomes a model of compassion and attunement, demonstrating that even when life feels meaningless, connection and transformation remain possible.

Meaning, Hope, and Connection

One of the core insights of transpersonal psychology is that meaning is not something imposed from outside but discovered within and between. For individuals struggling with suicidality, reconnecting to meaning may involve relationships, creativity, service, or spirituality. It may also involve reinterpreting suffering itself as part of the human journey.

Even when pain remains, the presence of meaning can act as a lifeline. Viktor Frankl observed that people could endure unimaginable hardship when they had a why to live for. Transpersonal psychology takes this insight seriously and creates therapeutic pathways for people to discover or rediscover their why.

Integrating Transpersonal Approaches With Other Therapies

While transpersonal psychology provides unique insights, it is often most effective when combined with other therapeutic approaches. Integration ensures that clients are not left with abstract ideas but are supported with practical tools, relational healing, and broader frameworks of hope. Different modalities complement one another in ways that strengthen both immediate crisis care and long-term meaning-making.

-

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). CBT helps clients identify and challenge negative thought patterns that fuel hopelessness. When paired with transpersonal work, CBT provides the tools to manage day-to-day thinking while transpersonal therapy explores deeper existential and spiritual questions.

-

Trauma-Informed Therapy. Many people experiencing suicidality carry histories of childhood adversity or relational trauma. Trauma-informed care prioritizes safety and stabilization, ensuring that clients are not retraumatized. Once safety is established, transpersonal practices can gently explore spirituality and meaning as part of long-term healing.

-

Narrative Therapy. Narrative approaches help clients rewrite the personal stories they tell about themselves. Combined with transpersonal psychology, narrative work can shift identity from “I am broken” to “I am on a journey of growth” while also connecting those stories to larger spiritual or cultural narratives that reinforce resilience.

-

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). DBT teaches skills for emotion regulation, mindfulness, and distress tolerance, which are crucial in moments of acute suicidal crisis. These skills create stability, making it possible to engage in deeper transpersonal exploration without becoming overwhelmed.

-

Existential Therapy. Existential therapists focus on freedom, choice, responsibility, and meaning. Transpersonal psychology expands this by adding dimensions of transcendence, spirituality, and connection to the sacred or collective, broadening the existential framework.

-

Somatic and Body-Based Therapies. Practices that integrate the body, such as somatic experiencing or yoga-informed therapy, help regulate the nervous system. Transpersonal approaches build on this foundation by exploring how bodily experiences can open into states of awe, flow, and spiritual connection.

-

Creative Arts Therapies. Music therapy, art therapy, and drama therapy provide ways to express and process pain when words are not enough. Transpersonal psychology emphasizes how these creative states can connect individuals with transcendent experiences, providing moments of relief and expanded awareness.

-

Family and Community-Based Therapies. Healing does not happen in isolation. Approaches such as family systems therapy or community-based interventions rebuild belonging and relational safety. Transpersonal work complements this by situating individuals within even larger networks of meaning such as culture, nature, or spirituality.

Together, these therapies form a comprehensive framework. Practical approaches like CBT and DBT stabilize the present moment. Trauma-informed and somatic therapies help resolve the past. Narrative and existential therapies reframe identity and choice. Transpersonal psychology brings in meaning, creativity, and spirituality, ensuring that healing is not only about survival but also about transformation and connection.

By honoring both the immediate needs of crisis and the long-term quest for meaning, integrated therapy helps people discover that despair does not have to be the final word.

Our therapists often integrate multiple modalities including transpersonal therapy.

Find a therapist in our directory today.

FAQ About Transpersonal Psychology and the Search for Meaning Beyond Suicidality

How does a transpersonal therapist assess suicide risk differently from a standard assessment?

A transpersonal assessment includes the usual questions about intent, plans, means, history of attempts, substance use, and protective factors. It also explores spiritual and existential variables that often go unaddressed. Clinicians ask about loss of meaning, spiritual despair, moral injury, and experiences that feel sacred or uncanny. They differentiate a spiritual emergency from psychosis, and they evaluate whether religious beliefs increase hope or increase shame. The map that emerges includes both clinical drivers and meaning based drivers so the safety plan can speak to the whole person.

What is the difference between a spiritual emergency and psychosis, and why does it matter for suicide risk?

A spiritual emergency is an intense opening to transpersonal material that outruns a person’s capacity to cope. It can include unusual perceptions, powerful emotions, or a sense of unity. Psychosis involves disturbances in reality testing that impair safety and function. The two can overlap which is why careful evaluation is essential. In suicide care the distinction matters because a spiritual emergency may respond to containment, grounding, and skilled integration, while psychosis may require medical treatment, medication, and a higher level of care. Transpersonal therapists collaborate with psychiatrists and medical providers so that meaning and safety are both honored.

Is transpersonal therapy only for religious or spiritual clients?

No. Transpersonal simply means extending beyond the narrow individual self. Secular clients often work with wonder, values, creativity, community, and connection with nature. For some, deep meaning is found in service, art, science, or family legacy. The therapist adapts language so it fits the client’s worldview. The goal is not to install beliefs but to help the client discover sources of purpose that feel authentic and workable.

Can medication be part of a transpersonal approach to suicidality?

Yes. Medication can reduce depression, anxiety, or agitation so that the person can do the work of meaning making without drowning in symptoms. Transpersonal clinicians frame medication as a tool that supports consciousness and choice rather than an enemy of spirituality. They coordinate with prescribers, consider interactions with practices such as breathwork or intensive meditation, and help clients track whether improved sleep and energy are increasing access to hope and connection.

What about psychedelic assisted therapy. Is it relevant and is it safe for people with suicidal thoughts?

Psychedelic work is a developing area with strict legal and ethical boundaries. For some people, carefully screened and professionally guided sessions have led to powerful experiences of connection and meaning. At the same time, these states can be destabilizing, especially when there is active suicidality, bipolar spectrum conditions, or trauma without sufficient stabilization. A responsible transpersonal therapist will never encourage do it yourself use, will discuss jurisdiction and legality, will screen for risk, and will emphasize extended integration sessions. The principle is simple. First safety and stabilization, then transformation.

How does a transpersonal safety plan differ from a standard safety plan?

Both plans include practical steps such as removing or locking away lethal means, identifying crisis supports, and listing warning signs. A transpersonal plan adds meaning based anchors. Clients may write a personal vow or line of scripture that keeps them tethered, build a ritual for moments of overwhelm, identify a place in nature that renews them, and list people who hold them in community. The plan becomes not only a checklist for danger but a compass that points toward belonging and purpose when the mind is fogged by despair.

What are signs that transpersonal therapy is helping with suicidality?

People often report more space around suicidal thoughts and less identification with them. There is a growing ability to name meaning threats without collapsing, and an increased capacity to seek connection before a crisis peaks. Body states shift more quickly from panic or numbness toward grounded presence. The person resumes or discovers practices that feel nourishing, such as creative work or time outdoors. Most importantly, setbacks are met with repair and learning rather than shame and isolation.

How do dreams, symbols, and imagery fit into suicide recovery without romanticizing danger?

Dreams and symbols can reveal where the psyche is stuck and where it is trying to heal. A nightmare might point to a part of the self that feels exiled or a situation that requires boundary or change. Therapists help clients work with images in a titrated way, for instance through drawing or journaling, so that meaning can be harvested without re traumatization. If self destructive themes emerge, they are not glorified. They are translated into specific needs such as protection, recognition, or rest, and those needs are addressed through practical actions and supportive relationships.

How does culture shape transpersonal work when suicide is on the table?

Culture informs what counts as sacred, what narratives of suffering are available, and what kinds of help feel safe. Some clients draw strength from religious communities, while others carry wounds from religious exclusion or spiritual abuse. Transpersonal therapy is culturally humble. It asks what meanings and practices sustain the client’s people and what harms have been done in the name of belief. The work may involve reclaiming ancestral rituals or creating new ones that honor identity without repeating old injuries.

What if spirituality has been used against me. Can transpersonal work still help?

Yes. Many people have experienced spiritual manipulation or shame. Transpersonal therapy does not require returning to those contexts. It begins by validating the injury and rebuilding trust. Meaning can be found in places that are not tied to the source of harm, for example in art, nature, service, or secular contemplative practice. The therapist is alert to spiritual bypass and will help separate genuine inspiration from pressure to be positive or compliant.

Can group work be done safely within a transpersonal frame for people who have suicidal thoughts

Group work can offer powerful belonging, shared language, and rituals of renewal. Safety requires clear screening, structure, confidentiality, and explicit crisis protocols. Groups may focus on mindfulness, nature based practice, creative process, or meaning making conversations. Facilitators should have training in suicide risk management, cultural humility, and transpersonal methods, and they should have a clear plan for individual follow up when someone becomes unstable. The aim is community that heals rather than intensity that overwhelms.

How is teletherapy adapted for transpersonal work with suicide risk?

Therapists co create rituals of arrival and closing to mark the session boundary, for example a brief breathing practice at the start and a grounding check at the end. They address privacy and safety up front, including who is nearby if a wellness check is needed. Therapists may invite nature connection by having the client orient to light, plants, or a window view, and they may use digital tools for guided imagery or journaling between sessions. The relational field is still the anchor. Technology simply becomes the pathway.

How do clinicians protect against spiritual bypass while still encouraging hope and transcendence?

They track both wings at once. On one wing, the therapist invites experiences of awe, purpose, and connection. On the other wing, the therapist insists on contact with concrete realities, including grief, anger, and unfinished trauma. If a client uses spiritual language to avoid pain, that pattern is named with care. The message is that inspiration and accountability belong together. Hope that refuses to feel does not heal.

What guidance does transpersonal therapy offer to family members or partners who want to help?

Loved ones are invited into the work of meaning and belonging, not only the work of monitoring risk. Families learn to reflect back the person’s values, to participate in simple rituals that promote connection, and to speak language that counters burdensomeness. They also learn limits and self care so support does not become rescue. When it is appropriate, the therapist facilitates conversations that repair injury and rebuild trust, which directly reduces suicide risk.

How does transpersonal therapy address social forces that fuel despair such as isolation, discrimination, or economic stress?

Transpersonal does not mean private and apolitical. Many people lose meaning when they face repeated injustice or disconnection at a societal level. Therapists help clients locate sources of dignity and solidarity, which can include advocacy, community service, or cultural renewal. The message is that purpose grows when we act in alignment with our deepest values, even when external conditions are slow to change.

How can I vet a transpersonal therapist if suicide is a concern?

Ask about training in suicide risk assessment, crisis response, and collaboration with medical providers. Ask how they would differentiate a spiritual emergency from psychosis and what steps they take when safety is in question. Inquire about experience integrating transpersonal work with modalities such as CBT, DBT, trauma treatment, or family therapy. Look for respect for your worldview, clear boundaries, consent for any altered state practices, and a plan for after hour support or referral. Red flags include pressure to adopt a belief system, avoidance of practical safety planning, or minimization of suicidal risk.

What does aftercare look like once the immediate crisis has passed?

Aftercare combines three strands. First, continued skills for regulation and relapse prevention. Second, ongoing integration of meaning practices, such as meditation, creativity, service, or spiritual community. Third, attention to life structure such as sleep, work, relationships, and health that sustains energy and hope. Review of the safety plan is routine, and small rituals of gratitude or remembrance can mark progress. The aim is a life that is not only safer but also more deeply worth living.