Suicide is often framed as an individual mental health challenge, yet the reality is far more complex. Social, cultural, and systemic factors shape who is most at risk, who has access to care, and who feels supported in times of crisis. Suicide prevention through the lens of anti-oppressive practice invites us to consider how structural inequities, discrimination, and marginalization contribute to despair. It also calls for practices that empower individuals and communities by centering justice, equity, and dignity.

Find a Therapist

What Is Anti-Oppressive Practice?

Anti-oppressive practice is a framework used across social work, counseling, and mental health fields. It emphasizes the need to identify and challenge systems of oppression that affect people’s well-being. These systems may include racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, and other forms of marginalization.

Rather than focusing solely on individual pathology, anti-oppressive practice acknowledges the broader context in which distress occurs. It views suicide risk not simply as a personal failing or weakness but as an understandable response to systemic forces that create isolation, discrimination, and lack of opportunity.

Why Oppression Matters in Suicide Prevention

Research consistently shows that marginalized groups experience higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts. For example, LGBTQ+ youth are significantly more likely to report suicidal thoughts compared to their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Indigenous communities often face elevated suicide rates, linked to historical trauma and ongoing systemic neglect. People of color, immigrants, individuals with disabilities, and those living in poverty may also face disproportionate risks.

Understanding suicide prevention through the lens of anti-oppressive practice means recognizing that these disparities are not accidental. They are the result of systemic inequities that compound individual struggles with layers of social exclusion.

Intersectionality and Suicide Risk

No single identity defines a person’s experience of oppression. Intersectionality, a concept introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw, reminds us that overlapping identities can intensify vulnerability. For instance, a Black transgender woman may face racism, transphobia, sexism, and economic hardship simultaneously. These intersecting forms of oppression magnify stress and increase suicide risk.

Anti-oppressive suicide prevention takes intersectionality seriously. It asks not only “what is this person struggling with individually” but also “how do their social locations and experiences of oppression shape their risk and their access to support.”

The Role of Power in Mental Health Care

Mental health systems themselves are not immune to oppressive dynamics. Many individuals report feeling unheard, dismissed, or pathologized by providers who do not understand their cultural context or lived experiences. For example, people of color may encounter racial bias in diagnosis and treatment, while LGBTQ+ clients may feel pressure to hide aspects of their identity.

Suicide prevention through the lens of anti-oppressive practice requires clinicians to reflect critically on their own use of power. This includes examining biases, ensuring representation in mental health professions, and collaborating with clients in ways that honor their agency. It shifts the role of the therapist from authority figure to ally.

Community-Centered Approaches

Anti-oppressive practice emphasizes that healing does not occur in isolation. Communities play a vital role in suicide prevention. Grassroots organizations, cultural centers, mutual aid networks, and peer support groups often provide resources and belonging in ways that mainstream mental health systems cannot.

Effective suicide prevention involves supporting these community-based efforts and ensuring that funding and recognition extend beyond traditional medical models. When communities are resourced to care for their members, suicide risk decreases.

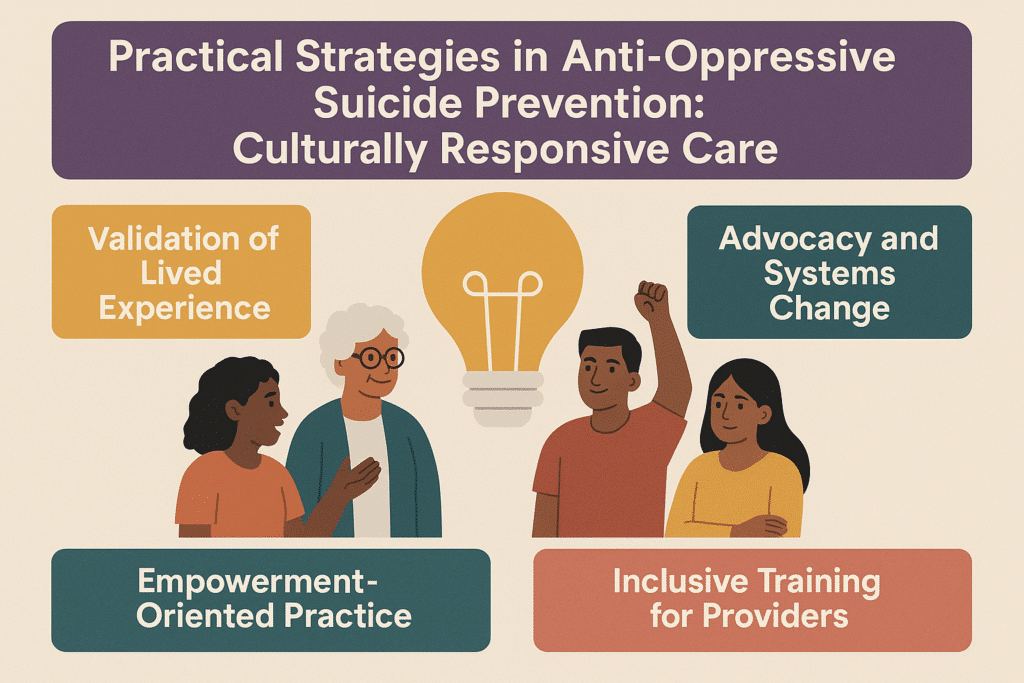

Practical Strategies in Anti-Oppressive Suicide Prevention

Applying anti-oppressive principles to suicide prevention involves several key strategies:

- Culturally Responsive Care: Therapists and organizations must tailor interventions to align with the cultural identities of clients. This includes incorporating language access, cultural rituals, and acknowledgment of systemic barriers.

- Validation of Lived Experience: Clients benefit from providers who affirm their realities rather than minimizing them. Naming systemic oppression helps clients feel understood and less isolated.

- Advocacy and Systems Change: Suicide prevention is not only clinical but also political. Advocating for policies that address housing insecurity, healthcare access, and discrimination is essential.

- Empowerment-Oriented Practice: Encouraging clients to identify and use their strengths fosters resilience. Empowerment also involves helping clients reclaim agency in systems that may have silenced them.

- Inclusive Training for Providers: Ongoing education in anti-racism, LGBTQ+ affirmation, disability justice, and cultural humility ensures that therapists remain accountable to diverse communities.

Why This Perspective Matters

Without an anti-oppressive lens, suicide prevention risks oversimplifying despair as an individual mental health problem. This misses the broader social conditions that drive hopelessness. By contrast, anti-oppressive practice reframes suicide prevention as a collective responsibility rooted in justice and compassion.

This perspective not only validates the struggles of marginalized individuals but also highlights the systemic changes needed to prevent despair from taking root. It invites us to imagine a future where mental health care is not just accessible but also affirming and liberating.

Moving Forward

Suicide prevention requires more than crisis hotlines and individual therapy sessions. It requires dismantling systems of oppression that create despair in the first place. Anti-oppressive practice provides a framework for both immediate support and long-term transformation.

If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts, the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline is available for immediate support. For ongoing care, therapy can provide a safe, affirming, and justice-oriented space for healing.

At our practice, most of our associate therapists work from an anti-oppressive lens. We invite you to browse our therapist directory and connect with a provider who can support you with care that acknowledges both personal experiences and systemic realities.

FAQ About Suicide Prevention Through the Lens of Anti-Oppressive Practice

How does anti-oppressive practice reshape the understanding of suicide?

Anti-oppressive practice invites us to see suicide not as a purely individual issue but as one deeply shaped by the environments people live in. This perspective asks providers and communities to notice how structural inequities, discrimination, and systemic neglect create conditions where despair can grow. By reframing suicide within these contexts, the focus shifts from blaming individuals to addressing barriers and building pathways to dignity and belonging.

Why is it important to connect systemic oppression with suicide prevention?

Oppression is not a background factor but a direct contributor to despair. Experiences of racism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, or class-based discrimination can leave individuals feeling unseen and unsupported. Suicide prevention becomes more effective when it acknowledges that these experiences are not incidental but central to understanding why some groups carry heavier risks. Validating these realities also helps reduce shame, fostering spaces where individuals feel safe to seek help.

How does intersectionality add complexity to suicide risk?

Intersectionality reminds us that people carry multiple identities that shape their lived experiences. A person navigating racism, sexism, and homophobia simultaneously will experience layers of stress and exclusion that cannot be separated. In suicide prevention, this means recognizing that risk factors compound and that care must be attuned to the full spectrum of someone’s identity. Affirming all aspects of a person’s self is not only respectful but also protective against despair.

What role do power dynamics play in mental health care?

Power in mental health care can either be healing or harmful. Too often, marginalized clients feel dismissed, misdiagnosed, or pressured to conform to standards that ignore their lived realities. Anti-oppressive practice calls for therapists to examine their own biases, share power with clients, and create collaborative spaces of care. When clients experience therapy as a partnership instead of a hierarchy, they are more likely to feel empowered, validated, and safe.

How can communities contribute to suicide prevention?

Communities can provide belonging and care in ways that traditional clinical systems sometimes cannot. Mutual aid groups, cultural organizations, and grassroots movements often offer practical resources, advocacy, and emotional support grounded in shared experience. These spaces reduce isolation and affirm identity. Suicide prevention that invests in community efforts is not only about immediate crisis intervention but also about building networks of resilience and justice.

What practical strategies can providers use to apply anti-oppressive principles?

Providers can adapt their practice by offering culturally responsive care, validating systemic realities, and advocating for clients within larger systems. This might mean providing therapy in a client’s first language, acknowledging how discrimination shapes daily stress, or connecting clients with community supports. Empowerment-oriented approaches encourage clients to reclaim agency, while ongoing provider training in cultural humility ensures care evolves with diverse needs.

How does validating lived experience support suicide prevention?

When clients hear their struggles named and acknowledged, it reduces feelings of isolation and self-blame. Saying aloud that systemic oppression is real and painful can be profoundly healing. Validation communicates that distress is not a personal weakness but a human response to unjust conditions. This shift helps clients feel less alone, more understood, and more open to healing.

What systemic changes are needed for sustainable suicide prevention?

True prevention requires more than therapeutic intervention. It means dismantling inequities that perpetuate despair. Access to safe housing, healthcare, education, and employment are not luxuries but necessities for mental well-being. Advocacy at policy and institutional levels is essential to reduce suicide risk across entire populations. Sustainable prevention is rooted in creating conditions where people not only survive but thrive with dignity.