Reviewed by Kathryn Vercillo, MA Psychology | Last Updated: January 2026

What is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy?

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT, pronounced as one word) is an evidence based psychological approach that uses acceptance, mindfulness, and behavior change strategies to increase psychological flexibility. Rather than fighting unwanted thoughts and feelings, ACT helps you develop a different relationship with internal experience while taking action toward what matters most to you.

Moving Toward What Matters When Struggle Feels Inescapable

You have probably spent considerable energy trying to feel different than you do. Attempting to think away anxiety, reason through depression, or distract from painful memories. These efforts seem logical: if something hurts, you should try to make it stop. Yet for many people, the struggle to eliminate unwanted internal experiences actually amplifies suffering and prevents meaningful living.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy offers a fundamentally different approach. Instead of fighting to change what you think and feel, ACT helps you change your relationship with thoughts and feelings so they no longer control your behavior. You learn to make room for difficult experiences while simultaneously moving toward values that give your life meaning and purpose.

At Center for Mindful Therapy, our Associate Marriage and Family Therapists bring ACT training to clients throughout California via telehealth and to Bay Area residents through in person sessions in San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, and surrounding communities. This accessibility means that wherever you are in California, values driven therapy that embraces life’s inevitable struggles can become part of your journey.

What distinguishes ACT from other therapies is its focus on psychological flexibility rather than symptom elimination. While symptom reduction often occurs, the primary goal is building your capacity to be present, open to experience, and engaged in meaningful action regardless of what shows up internally. This shift liberates you from the exhausting battle against your own mind.

Our therapists work within a supervised model that ensures quality care while making specialized treatment accessible. Each Associate MFT receives individual clinical supervision, combining current training in ACT principles with guidance from experienced clinicians.

Browse our Therapist Directory

On This Page:

- Understanding ACT’s Unique Approach

- The Six Core Processes of ACT

- Psychological Flexibility as the Goal

- Conditions ACT Effectively Addresses

- ACT Techniques and Exercises

- ACT Compared to Other Approaches

- Beginning Your ACT Journey

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding ACT’s Unique Approach

Origins in Relational Frame Theory

ACT emerged from a theory about how human language and cognition work called Relational Frame Theory (RFT). Developed by Steven Hayes and colleagues beginning in the 1980s, RFT explains how language enables humans to suffer in unique ways by creating symbolic connections that trigger pain even in the absence of direct experience.

Consider how hearing a song can instantly evoke the heartbreak of a relationship ended years ago. Or how anticipating a difficult conversation tomorrow can produce anxiety equal to the conversation itself. Language and thought allow you to experience pain across time and space, to suffer from memories of the past and fears of the future, to feel inadequate when comparing yourself to imagined standards.

This capacity is not a malfunction but a feature of human cognition. The same abilities that enable planning, problem solving, creativity, and connection also enable rumination, worry, and symbolic suffering. You cannot simply turn off these capabilities without losing what makes you human.

ACT accepts this reality and works with it rather than against it. Since you cannot stop your mind from producing painful content, ACT teaches you to relate differently to that content so it loses its power to control your life.

The Problem with Control

Most people assume that psychological health means controlling internal experience, feeling good, thinking positively, and eliminating distressing emotions. This assumption leads to constant struggle against unwanted thoughts and feelings.

ACT identifies this control agenda as itself a source of suffering. When you try to suppress, avoid, or eliminate internal experiences, several problems emerge. First, suppression often does not work, or works only temporarily. Trying not to think about something frequently increases how much you think about it. Second, avoidance strategies prevent you from living fully, shrinking your life to avoid triggering unwanted experiences. Third, the struggle itself consumes energy and attention that could go toward building a meaningful life.

ACT proposes an alternative: acceptance of internal experience combined with commitment to valued action. Rather than waiting to feel better before living your life, you learn to take your mind with you wherever you go, thoughts and feelings and all, while moving toward what matters.

This does not mean passive resignation or wallowing in misery. Acceptance in ACT is active and purposeful, making room for experience in service of living fully rather than being pushed around by efforts to escape discomfort.

Values as the Compass

Central to ACT is clarifying what you truly care about, your values, and using these as a compass for action. Values are not goals you achieve and check off but ongoing directions you can move toward indefinitely. Kindness is a value; performing a specific kind act is a goal. Creativity is a value; completing a particular project is a goal.

When your life aligns with your values, it feels meaningful even when difficult. When you abandon values to chase comfort or escape discomfort, life feels empty even when comfortable. ACT helps you identify your values and organize your behavior around them, choosing direction based on what matters rather than what feels easiest.

This values orientation provides motivation for acceptance. Making room for anxiety makes sense when doing so allows you to pursue a valued relationship. Tolerating uncertainty becomes worthwhile when it enables meaningful career changes. Values give purpose to the willingness ACT cultivates.

Clinical research published in the World Journal of Surgical Oncology demonstrates ACT’s profound impact on quality of life and sense of meaning. In a randomized controlled trial, participants receiving ACT showed significant improvements in psychological wellbeing, emotional regulation, and their sense of meaning in life compared to control groups. These findings suggest that ACT’s values oriented approach helps people reconnect with what matters most, even during challenging life circumstances.

The Six Core Processes of ACT

ACT organizes its approach around six interrelated processes that together create psychological flexibility. These processes work as pairs addressing different aspects of the flexibility needed for vital living.

Acceptance and Cognitive Defusion

These two processes change your relationship with unwanted internal experiences.

Acceptance involves actively making room for thoughts, feelings, sensations, and urges rather than trying to escape, avoid, or control them. This is not tolerating in a gritted teeth way but genuinely allowing experience to be present without struggle. Acceptance does not mean liking or wanting what you feel but simply letting it be there while you direct your energy elsewhere.

Cognitive defusion involves stepping back from thoughts to observe them rather than being caught up in them. When fused with a thought, you experience it as literal truth that demands response. When defused, you can notice having the thought without being controlled by it. The thought “I am worthless” becomes “I am having the thought that I am worthless,” which allows different relationship and different action.

These processes address the experiential avoidance and cognitive fusion that cause much human suffering. When you can accept what shows up internally and defuse from unhelpful thoughts, you reclaim freedom to act based on choice rather than reaction.

Contact with the Present Moment and Self as Context

These processes develop your capacity to be present and observe experience from a stable perspective.

Contact with the present moment means bringing flexible, voluntary attention to what is happening right now rather than being lost in mental time travel to past or future. This present moment awareness allows you to respond to actual current circumstances rather than reacting to memories or predictions.

Self as context refers to developing a stable sense of self that observes experience rather than being synonymous with it. From this perspective, you can notice thoughts, feelings, and sensations without becoming them. You are the context in which experiences occur, not the experiences themselves. This observer self provides continuity and stability even as the content of experience constantly changes.

These processes create the awareness and perspective needed for choosing response rather than automatic reaction. Present moment contact and observer self provide the platform from which acceptance and defusion become possible.

Values and Committed Action

These processes orient you toward meaningful living and translate values into behavior.

Values clarification involves identifying what truly matters to you, what you want your life to stand for, what qualities you want to embody in your actions. Values are freely chosen directions rather than externally imposed obligations. They emerge from your authentic self rather than from what others expect.

Committed action means taking concrete steps in valued directions regardless of internal obstacles. This involves setting goals that serve values, taking action even when difficult thoughts and feelings show up, and persisting when obstacles arise. Commitment includes willingness to fail and try again, understanding that valued living involves ongoing action rather than single decisions.

These processes provide direction and motivation. Values answer “toward what?” while committed action translates values into actual living. Without values, acceptance has no purpose. Without committed action, values remain abstract rather than lived.

The Hexaflex Model

ACT often represents these six processes in a hexagonal diagram called the hexaflex. Each process occupies one point of the hexagon, with psychological flexibility at the center. Lines connect related processes: acceptance with defusion, present moment with self as context, values with committed action.

The hexaflex illustrates that psychological flexibility involves all six processes working together. Strength in one area cannot compensate for deficits in another. Comprehensive ACT addresses all processes while potentially emphasizing particular areas based on individual needs.

The hexaflex also shows that movement on any process affects the whole system. Improving defusion often facilitates acceptance. Clarifying values motivates committed action. The processes reinforce each other in virtuous cycles.

Psychological Flexibility as the Goal

Defining Psychological Flexibility

Psychological flexibility is the ability to be present, open, and do what matters. It involves holding your thoughts and feelings lightly while engaging in action guided by your values. When psychologically flexible, you can adapt to changing circumstances, shift perspective when helpful, balance competing desires, and persist or change course as situations require.

Flexibility stands in contrast to psychological rigidity: being stuck in patterns, controlled by thoughts and feelings, unable to adapt to changing circumstances, and alienated from values by efforts to avoid discomfort. Rigidity underlies much psychological suffering and interferes with effective living.

A systematic review published in the Annals of Neurosciences confirms that the distinctive nature of ACT emphasizes psychological flexibility, mindfulness, and actions rooted in personal values. The review found that ACT consistently reduces symptom severity, improves emotional regulation, enhances life satisfaction, and increases psychological flexibility across a wide range of mental health conditions.

ACT aims to increase flexibility rather than eliminate symptoms, though symptom reduction often accompanies increased flexibility. When you can hold difficult experiences lightly while taking valued action, the experiences themselves often become less frequent or intense. More importantly, they matter less because they no longer control your life.

Flexibility Versus Symptom Elimination

Traditional therapy often measures success by symptom reduction: less anxiety, fewer depressive episodes, decreased frequency of unwanted behaviors. ACT takes a different approach, measuring success by increased engagement in meaningful living.

This shift matters for several reasons. First, focusing on symptoms can paradoxically maintain them by keeping attention on what you are trying to eliminate. Second, waiting for symptoms to resolve before living fully means potentially waiting forever. Third, a meaningful life often involves experiences that symptom focused approaches would label as problems: the anxiety of taking risks, the grief of loving deeply, the discomfort of growth.

ACT does not oppose symptom reduction but positions it as a frequent byproduct rather than the primary goal. Many ACT clients experience significant symptom improvement, but this occurs through changed relationship with symptoms rather than through direct symptom fighting.

The Workability Question

ACT evaluates strategies and behaviors based on workability: does this approach help you live a valued life? Rather than judging thoughts as true or false, rational or irrational, ACT asks whether buying into a thought helps you move toward what matters.

A thought might be technically accurate yet unhelpful when fused with it. The thought “I might fail” may be true (failure is always possible) but acting on it by avoiding challenges prevents valued living. Conversely, motivation through self criticism might produce short term results but at costs that undermine long term wellbeing.

Workability provides a pragmatic alternative to debates about truth or rationality. Your therapist helps you evaluate your strategies based on their effects in your life rather than their logical status. Does this approach help you be who you want to be and do what you want to do?

Conditions ACT Effectively Addresses

ACT has accumulated substantial research support across diverse conditions. The flexibility model applies broadly because psychological rigidity contributes to many forms of suffering. A systematic review in the journal Healthcare examined ACT’s effectiveness across psychiatric populations and found that the approach enhances social functioning and interpersonal relationships while reducing psychiatric symptoms. The research highlighted ACT’s particular value for conditions involving social impairment, noting that psychological flexibility facilitates adaptive responses to life’s challenges by helping individuals navigate difficult emotions without becoming overwhelmed by them.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety involves experiential avoidance and fusion with threat related thoughts. You may organize your life around avoiding anxiety triggers, shrinking your world to escape discomfort. Anxious thoughts become commands: “If this could go badly, avoid it.”

ACT addresses anxiety by changing your relationship with anxious experience rather than trying to eliminate anxiety. You learn to accept anxious sensations rather than fighting them, defuse from anxious thoughts rather than treating them as facts, and take valued action even when anxiety shows up.

Research supports ACT for generalized anxiety, social anxiety, panic disorder, and specific phobias. Outcomes often compare favorably to established treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy while using different mechanisms of change.

California residents managing anxiety find ACT particularly valuable because the approach does not require eliminating anxiety before living fully. You can pursue meaningful career opportunities, relationships, and experiences while carrying anxiety with you rather than waiting until you feel confident.

Depression

Depression often involves fusion with self critical thoughts, rumination about the past, hopelessness about the future, and withdrawal from valued activities. The control agenda manifests as trying to think your way out of depression or waiting to feel motivated before taking action.

ACT addresses depression through multiple processes. Defusion reduces the impact of self critical and hopeless thoughts. Acceptance makes room for painful feelings without being consumed by them. Values clarify what matters even when depression insists nothing does. Committed action involves taking steps toward values despite low motivation, building momentum through behavior rather than waiting for internal change.

The behavioral activation component of ACT for depression moves you toward engagement even when you do not feel like it. Values provide the compass for where to engage. Gradually, valued action rebuilds positive reinforcement while proving depression’s predictions wrong.

Research published in Psychiatry Research supports these clinical observations. A recent meta analysis examining randomized controlled trials found that ACT significantly alleviates both depressive and anxiety symptoms in individuals with depression while simultaneously improving psychological flexibility. The analysis also revealed that group ACT formats appeared particularly effective, offering a social component that may enhance treatment outcomes.

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain creates particular challenges because pain cannot be simply eliminated through willpower or positive thinking. Attempts to control pain often backfire, creating additional suffering through frustration, depression, and life restriction.

ACT for chronic pain emphasizes acceptance of pain sensations while maintaining engagement in valued activities. Rather than waiting for pain to resolve before living, you learn to carry pain with you into a meaningful life. Defusion addresses the thoughts that amplify suffering: catastrophizing, comparing to life before pain, despairing about the future.

Research strongly supports ACT for chronic pain, with improvements in functioning, mood, and quality of life even when pain intensity itself does not change. For many pain sufferers, this functional approach provides more lasting benefit than continued pursuit of pain elimination.

Substance Use and Addiction

Substance use often represents experiential avoidance taken to extremes: using substances to escape unwanted internal experiences. The short term relief reinforces use while creating long term problems that generate more experiences to escape.

ACT addresses addiction by building tolerance for the experiences that substances were used to avoid. Acceptance skills help with cravings, withdrawal discomfort, and the emotions underlying use. Values clarification reveals what matters beyond the temporary relief substances provide. Committed action builds patterns of behavior aligned with values rather than driven by avoidance.

The approach also addresses relapse compassionately. Slips become occasions for recommitting to values rather than evidence of failure requiring self punishment. This non judgmental stance reduces shame spirals that often perpetuate relapse.

Obsessive Compulsive Patterns

OCD involves fusion with intrusive thoughts treated as meaningful, dangerous, or requiring response. Compulsions represent control strategies that temporarily reduce anxiety but maintain the disorder long term.

ACT addresses OCD through defusion from intrusive thoughts and acceptance of anxiety without performing compulsions. The approach complements exposure and response prevention by providing a framework for why exposures work and how to navigate the anxiety they produce.

ACT’s stance that thoughts are just thoughts, not facts requiring analysis or response, proves particularly valuable for OCD where the content of intrusions can seem uniquely horrifying. Learning to carry intrusions lightly while pursuing values directly counters the disorder’s demands for certainty and control.

Work Stress and Burnout

Work environments create unique pressures that can lead to burnout, disengagement, and values conflict. ACT principles apply to professional functioning just as they do to clinical conditions.

ACT for workplace stress involves clarifying work related values, accepting the inevitable difficulties of professional life, defusing from thoughts that create unnecessary suffering, and committing to engagement even when challenging. The approach helps with work/life balance, managing difficult colleagues, navigating organizational change, and finding meaning in imperfect situations.

Telehealth ACT serves California professionals who cannot easily attend in person sessions due to demanding schedules. Video sessions accommodate busy work lives while providing tools for managing professional stress.

Relationship Difficulties

Relationship problems often involve fusion with stories about partners, experiential avoidance of vulnerability or conflict, and values conflicts between connection and protection. ACT provides tools for relating differently to relationship challenges.

Acceptance allows difficult emotions about relationships to be present without demanding immediate resolution. Defusion creates distance from narratives that keep conflicts alive. Values clarification illuminates what you actually want from relationships versus what protective strategies have you pursuing. Committed action involves showing up in relationships consistent with values even when uncomfortable.

ACT can be done individually to address your patterns in relationships or with couples to help partners develop shared flexibility and values alignment.

ACT Techniques and Exercises

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy uses experiential exercises and metaphors to develop flexibility. Understanding key techniques illustrates how the approach works in practice.

Defusion Exercises

Defusion exercises help you step back from thoughts to observe rather than be consumed by them. These techniques do not evaluate thought content but change your relationship with thinking itself.

One common exercise involves repeating a troubling word until it loses meaning, becoming just sounds. Your therapist might have you repeat “I’m worthless” rapidly until it dissolves into syllables, demonstrating that words are sounds with arbitrary meanings you can hold lightly.

Another technique involves noticing thoughts with acknowledgment: “I notice I’m having the thought that…” This creates distance between you and the thought, allowing observation rather than fusion.

Thanking your mind for thoughts, singing thoughts to silly tunes, imagining thoughts as leaves floating down a stream, or visualizing placing thoughts on clouds all serve to create defusion through creative distancing.

Values Clarification Exercises

Values clarification helps you identify what truly matters to you, often hidden beneath layers of should and ought. These exercises access your authentic directions.

Your therapist might ask what you would want said at your funeral, revealing what you want your life to stand for. Or you might imagine your ideal eighteenth birthday, visualizing what life would look like if you lived fully according to your values.

Card sorts allow you to rank values in order of importance, revealing priorities. Writing exercises explore valued domains: relationships, work, health, community, spirituality, leisure, personal growth. Life compass exercises map current behavior against valued directions, illuminating gaps.

The sweet spot exercise identifies the intersection between what matters to you, what you are good at, and what the world needs. This integration locates meaningful direction grounded in reality.

Acceptance and Willingness Exercises

Acceptance exercises build capacity to have difficult experiences without struggle. These practices distinguish acceptance from tolerance or resignation.

Physicalizing exercises involve locating emotions in the body, describing their qualities (size, shape, color, temperature), and making room for them rather than fighting. You might breathe into areas of discomfort, expanding around sensations rather than contracting against them.

The struggle switch metaphor imagines a switch that controls how much you fight against internal experience. Noticing when the switch is on and practicing turning it off develops the ability to shift from struggle to acceptance.

Expansion exercises involve opening posture, softening muscles, and creating space internally for whatever is present. This physical opening facilitates psychological acceptance.

Present Moment Exercises

Present moment exercises develop attention that can flexibly focus on now rather than being hijacked by past or future.

Mindfulness practices like breath awareness, body scans, and sensory focusing build present moment attention. ACT uses these practices pragmatically rather than spiritually, developing attention as a skill in service of psychological flexibility.

Noticing exercises bring awareness to direct experience: five things you can see, four you can hear, three you can touch. This sensory grounding interrupts mental time travel and reconnects you with actual current experience.

The “being present versus being absent” distinction highlights moments when you are mentally elsewhere versus fully here. Catching yourself lost in thought and returning to now builds flexibility of attention.

Committed Action Exercises

Committed action translates values into concrete behavior through goal setting and action planning.

SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time bound) translate value directions into actionable steps. If connection is a value, a SMART goal might be scheduling weekly calls with a friend.

Willingness scales evaluate how willing you are to have difficult experiences in service of valued action. Rating your willingness on a zero to ten scale identifies resistance that might prevent action.

If/then planning prepares for obstacles: “If anxiety shows up when I start the conversation, then I will acknowledge it and continue.” Anticipating difficulties and planning responses increases follow through.

ACT Compared to Other Approaches

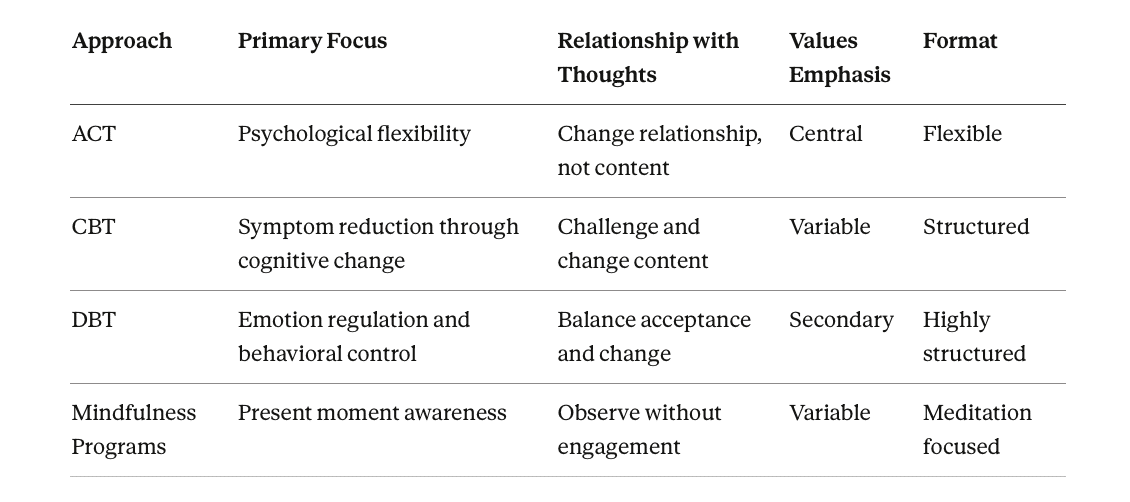

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and ACT

ACT and CBT share historical connections, both emerging from behavioral psychology traditions. Both emphasize empirical support, skill building, and active intervention. However, they differ significantly in approach.

CBT focuses on changing the content of thoughts: identifying cognitive distortions, challenging irrational beliefs, replacing negative thoughts with more adaptive ones. The assumption is that thoughts cause feelings and that changing thoughts changes feelings.

ACT does not attempt to change thought content but rather changes your relationship with thoughts. Rather than disputing whether a thought is accurate, ACT asks whether fusing with the thought helps you live according to your values. The same thought might be held lightly and observed rather than challenged and replaced.

Research comparing ACT and CBT for various conditions generally finds comparable outcomes through different mechanisms. Some clients prefer ACT’s acceptance stance while others prefer CBT’s direct cognitive challenge. Both approaches have strong evidence support.

ACT and DBT

ACT and DBT both incorporate acceptance and mindfulness while maintaining commitment to change. Both recognize that fighting internal experience often backfires. However, they differ in structure, emphasis, and target populations.

DBT is a comprehensive, structured treatment designed originally for borderline personality disorder. It includes specific skill modules, diary cards, phone coaching, and consultation teams. The focus on distress tolerance and emotion regulation emphasizes managing intense emotional states.

ACT is more flexible in format and applicable across diverse concerns. The emphasis on values and committed action focuses less on crisis survival and more on building meaningful life. While DBT addresses what to do when overwhelmed, ACT emphasizes how to live fully even when life is difficult.

For clients with severe emotional dysregulation or self harm, DBT’s structure and crisis focus may be more appropriate. For clients seeking values clarification and engagement in life, ACT’s flexibility orientation may fit better. Some clients benefit from both approaches at different treatment stages.

ACT and Mindfulness Based Approaches

ACT incorporates mindfulness but uses it differently than traditional mindfulness based approaches like MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction) or MBCT (Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy).

Traditional mindfulness programs often present meditation practice as central, with weeks of formal practice building skills. The orientation may include spiritual or contemplative dimensions.

ACT uses mindfulness pragmatically to develop present moment awareness and defusion, without requiring extensive formal meditation practice. The approach is explicitly secular and functional: mindfulness serves psychological flexibility rather than being an end in itself.

For those attracted to meditation practice, traditional mindfulness programs may appeal. For those seeking mindfulness benefits without extensive formal practice or spiritual framework, ACT offers a pragmatic alternative.

Beginning Your ACT Journey

Finding an ACT Therapist

Our therapist directory allows you to search for clinicians with ACT training. Read profiles carefully, noting training background, treatment approaches, and areas of specialization. ACT training varies from brief introductions to extensive certification, so understanding a therapist’s depth of training helps assess fit.

When contacting potential therapists, ask about their ACT training and experience. How central is ACT to their practice? Do they use other approaches alongside ACT? What populations have they worked with using this approach? These questions help you find someone with appropriate expertise.

For California residents outside the Bay Area, telehealth provides access to ACT trained therapists who might otherwise be geographically inaccessible. The convenience of video sessions accommodates busy schedules while providing evidence based treatment. ACT adapts well to telehealth delivery because the conversational and experiential nature of sessions translates effectively to video format. Exercises can be guided remotely, and homework review works identically whether in person or online.

Preparing for Treatment

ACT may differ from previous therapy experiences. Prepare by opening yourself to the possibility that changing your relationship with experience might help more than changing the experiences themselves. This does not require abandoning hope for symptom improvement but allowing that improvement might come through unexpected paths.

Consider what matters to you before your first session. What would make your life meaningful? Are there things that you have you given up while trying to feel better? What would you pursue if internal obstacles did not stop you? These reflections provide material for early sessions.

Your First Sessions

Initial sessions explore what brings you to therapy and introduce ACT principles. Your therapist learns about your history, current struggles, and what matters to you. They may use metaphors to illustrate key concepts: thoughts as passengers on a bus you are driving, difficult experiences as uninvited guests at a party, your mind as a not always helpful advisor.

ACT therapists use what they call creative hopelessness to compassionately explore whether your current approaches are creating the life you want. This is not about making you feel hopeless but about honestly examining whether control strategies have worked and at what cost. When you see clearly that fighting against experience has not succeeded, openness to alternatives emerges naturally.

Values clarification begins early, ensuring that acceptance and defusion skills serve meaningful ends. Understanding what matters provides context for why willingness is worth developing.

The Course of Treatment

ACT sessions blend experiential exercises with conversation. Your therapist might guide you through a defusion exercise, explore reactions, then connect the experience to your specific struggles and values. The work is active and collaborative rather than passive and prescriptive.

The six processes receive attention based on your needs. Some clients require extensive values clarification before meaningful committed action is possible. Others come with clear values but need help with defusion or acceptance to pursue them. Your therapist assesses where flexibility is most limited and targets intervention accordingly.

Homework extends learning between sessions. You might practice noticing thoughts without fusion, take committed actions toward values, or track willingness to have difficult experiences. This between session practice builds skills that session work alone cannot develop.

Progress and Outcomes

Progress in ACT looks like increased engagement in valued living, even when difficult internal experiences remain present. You might pursue relationships despite anxiety, return to creative work despite self doubt, or engage in life despite pain. The experiences may or may not decrease; what changes is their control over your behavior.

Your therapist tracks progress through conversation about your life and specific measures of flexibility, values alignment, and functioning. Unlike approaches measuring success by symptom reduction, ACT asks whether you are living more fully.

Treatment length varies based on presenting concerns and individual needs. Some clients achieve meaningful gains in eight to twelve sessions focused on specific issues. Others with more complex situations or broader goals benefit from longer engagement. ACT provides skills that continue developing after formal treatment ends, building capacities you carry forward independently rather than requiring indefinite treatment.

Some clients prefer starting with telehealth for convenience, then transitioning to occasional in person sessions for variety. Others maintain telehealth throughout, finding video delivery fully sufficient for their needs.

The Therapeutic Relationship

ACT therapists model the approach they teach. Your therapist accepts your experience as it is while also expecting you to move toward valued living. They hold their own thoughts lightly and demonstrate flexibility. The relationship itself illustrates ACT principles in action.

The therapeutic relationship provides safe context for practicing acceptance, defusion, and committed action. You might notice fusion or avoidance in session and explore these patterns with your therapist’s help. The relationship becomes a laboratory for developing flexibility that transfers to your broader life.

For questions about ACT or assistance finding the right therapist, contact us.

Browse our Therapist Directory

Frequently Asked Questions About ACT

Q: Does acceptance mean giving up on feeling better? Will I have to live with depression or anxiety forever if I accept it?

A: This is a common concern about ACT, but acceptance does not mean giving up or resigning yourself to suffering. Acceptance in ACT is active and purposeful: making room for difficult experiences in order to pursue what matters, not because suffering is good or change is impossible.

Here is the paradox many ACT clients discover: when you stop fighting against internal experience and accept it fully, the experiences often become less intense or frequent. Struggling against anxiety amplifies it; accepting anxiety often diminishes it. Not because you are trying to make it decrease (that would be another control strategy) but because struggle itself was adding to the problem.

More importantly, ACT acceptance is about where you put your energy. Rather than spending life fighting an internal battle, you redirect that energy toward valued living. Many ACT clients discover that meaningful life is possible even with depression or anxiety present. And that meaningful living itself often reduces the conditions that generate depression and anxiety.

Q: How is ACT different from just giving up and not trying to change anything?

A: ACT involves tremendous change, just not the kind most people initially pursue. Rather than trying to change internal experiences through direct manipulation, you change your relationship with those experiences and change your behavior toward values.

ACT is highly active. Committed action involves setting goals, taking steps, persisting through obstacles, and continuously moving toward what matters. Values driven living requires constant choice and effort. Acceptance itself is an active stance, not passive resignation.

What ACT asks you to stop is the exhausting, often futile struggle to directly control internal experience. This struggle consumes energy that could go toward building a meaningful life. Acceptance frees up resources for change that actually works: behavioral change guided by values rather than internal control that usually backfires.

Q: Will ACT work for my specific problem, or is it too philosophical to help with real symptoms?

A: ACT has substantial research support for diverse conditions including anxiety disorders, depression, chronic pain, substance use, obsessive compulsive disorder, workplace stress, and many others. The flexibility model applies broadly because psychological rigidity contributes to many forms of suffering.

ACT is not just philosophical discussion but practical skill building. You learn specific techniques for defusion, acceptance, present moment contact, and committed action. These skills apply directly to whatever symptoms you experience.

The philosophical framework matters because it provides context for skills. Understanding why acceptance helps motivates practice. Clarifying values provides direction for committed action. The framework and the practical techniques work together, neither adequate alone.

Research shows that ACT outcomes compare favorably to established treatments like CBT for many conditions while working through different mechanisms. Whether ACT suits your specific situation is best assessed through consultation with a trained therapist who can evaluate fit.

Q: I have trouble with mindfulness. Can I still benefit from ACT?

A: ACT uses mindfulness differently than meditation focused approaches. You do not need to become an accomplished meditator or achieve particular states of consciousness. ACT mindfulness is pragmatic: developing enough present moment awareness to notice what is happening, defuse from thoughts, and make choices rather than automatic reactions.

If you have struggled with traditional meditation, ACT might actually suit you better than mindfulness based approaches. The present moment exercises are often brief and integrated into daily life rather than requiring dedicated meditation sessions. The purpose is functional flexibility rather than spiritual attainment.

Your therapist can adapt mindfulness components to your needs and preferences. Some clients develop substantial formal practice through ACT while others achieve flexibility primarily through informal exercises. The goal is psychological flexibility, not mindfulness skill as an end in itself.

Q: How long does ACT treatment typically last?

A: Treatment length varies based on presenting concerns, individual needs, and goals. Some clients achieve meaningful gains in eight to twelve sessions focused on specific issues. Others with more complex situations or broader goals benefit from longer engagement.

ACT provides skills that continue developing after formal treatment ends. Unlike treatments requiring ongoing symptom management, ACT aims to build capacities you carry forward independently. The goal is not indefinite treatment but rather developing flexibility that sustains without professional support.

Your therapist discusses expected duration based on your specific situation and adjusts plans as treatment progresses. Progress toward valued living rather than arbitrary timeframes guides decisions about treatment completion.

Q: Can ACT work alongside medication, or do I need to choose one or the other?

A: ACT works well alongside medication for clients who benefit from pharmacological support. The approaches address different aspects of wellbeing and can complement each other effectively.

For some conditions, medication provides physiological stabilization that makes psychological work more accessible. For others, ACT skills reduce reliance on medication over time. Your therapist and prescriber can coordinate to optimize your overall treatment.

ACT does not require you to view medication as problematic or pursue treatment without it. Acceptance applies to the reality of your situation, including needing medication if you do. Values driven living includes taking care of your health in whatever ways work.

Q: I have tried other therapies without much success. What makes ACT different enough to potentially help me?

A: ACT differs fundamentally from approaches focused on controlling internal experience. If previous therapy targeted symptom elimination through cognitive challenge, behavior modification, or processing past experiences, ACT offers genuinely different mechanisms.

Many clients who struggled with other approaches find ACT’s acceptance stance transformative. After years of fighting against thoughts and feelings, permission to stop struggling provides relief itself. The shift from “how do I feel better” to “how do I live better” opens possibilities that symptom focus could not.

ACT also differs in emphasis on values. If previous therapy addressed problems without clarifying what you actually want from life, ACT’s values focus provides direction that was missing. Knowing why you are building flexibility motivates the work.

That said, ACT is not magic and does not help everyone. Discussing your previous therapy experiences with potential ACT therapists helps assess whether this approach might offer something different for your situation.

Related Therapy Services

- DBT: Dialectical Behavior Therapy shares acceptance principles while providing structured skill building for emotional regulation and distress tolerance.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: The related approach that emphasizes changing thought patterns, useful when cognitive restructuring fits your needs.

- Mindfulness Based Therapies: Approaches emphasizing meditation and present moment awareness that complement ACT principles.

- Anxiety Treatment: Specialized support for anxiety disorders using various evidence based approaches including ACT.

Citations:

- Kong, Q., Yan, S., Huang, K., Han, B., Han, R., Jiao, Y., Yang, H., Pu, Y., Li, S., & Jia, Y. (2025). The efficacy of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 352, 116701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2025.116701

- Aravind, A., Agarwal, M., Malhotra, S., & Ayyub, S. (2025). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy on mental health issues: A systematic review. Annals of Neurosciences, 32(4), 321-327. https://doi.org/10.1177/09727531241300741

- Latella, D., Marafioti, G., Formica, C., Calderone, A., La Fauci, E., Foti, A., Calabrò, R. S., & Filippello, G. (2025). The role of acceptance and commitment therapy in improving social functioning among psychiatric patients: A systematic review. Healthcare, 13(13), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131587

- Ruan, Y., Xie, W., & Xu, F. (2025). The effect of acceptance commitment therapy on the mental health of elderly breast cancer patients. World Journal of Surgical Oncology, 23, 398. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12957-025-04056-x